Ik schrik ervan hoe weinig ik 1-2-3 kan vinden over deze astronooom/kunstenaar… Maakte prachtig werk. Zo mooi dat ik het gehele boek alvast plaats, zonder het zelf al ergens in het echt ingezien te hebben. Volgt hopelijk later ook nog. Het boek is niet zo mooi als mijn grote favoriet Astronomicum Ceasareum, maar wel een prachtig werk 200 jaar later dan Apianus.

Wikipedia over Doppelmayer:

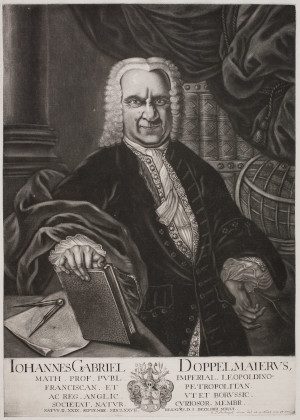

Johann Gabriel Doppelmayr, soms Doppelmayer of Doppelmair gespeld (Neurenberg, 27 september 1677 – aldaar, 1 december 1750), was een Duits wiskundige, astronoom en cartograaf.

Hij was de zoon van de koopman Johann Siegmund Doppelmayr die na het Aegidien-Gymnasium in Nürnberg in 1696 naar de ondertussen verdwenen Universiteit van Altdorf ging. Hij studeerde daar fysica, wiskunde en rechten in 1696. Als proefschrift schreef hij in 1698 over de zon.

Hij studeerde enige tijd aan de Martin-Luther Universiteit in Halle, waar hij tevens Frans en Italiaans leerde. Nadat hij zijn studie rechten beëindigde, reisde hij twee jaar lang en studeerde ondertussen. Hij bezocht meerdere steden in Duitsland, Nederland en Engeland, waaronder Utrecht, Leiden, Oxford en Londen.

Hij was leerkracht wiskunde aan het Aegidien-Gymnasium van 1704 tot aan zijn overlijden. Hij is bekend door zijn publicaties over natuurwetenschappen, wiskunde en astronomie, waaronder boldriehoeksmeetkunde, hemelkaarten en zonnewijzers.

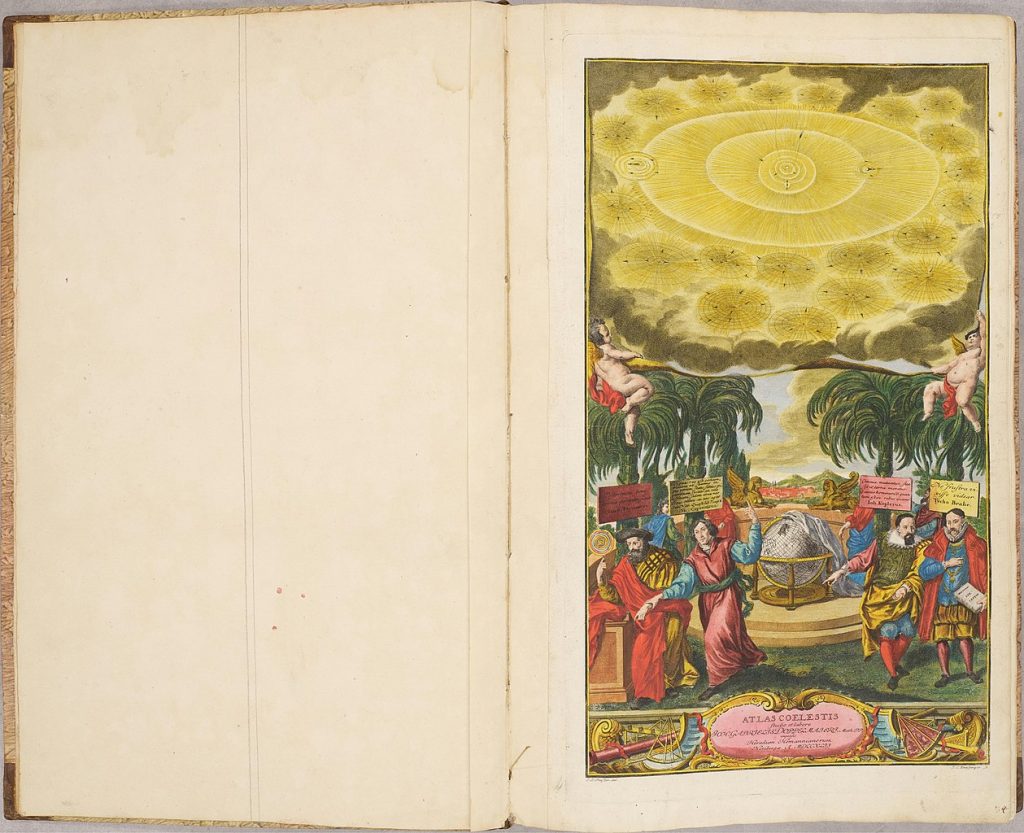

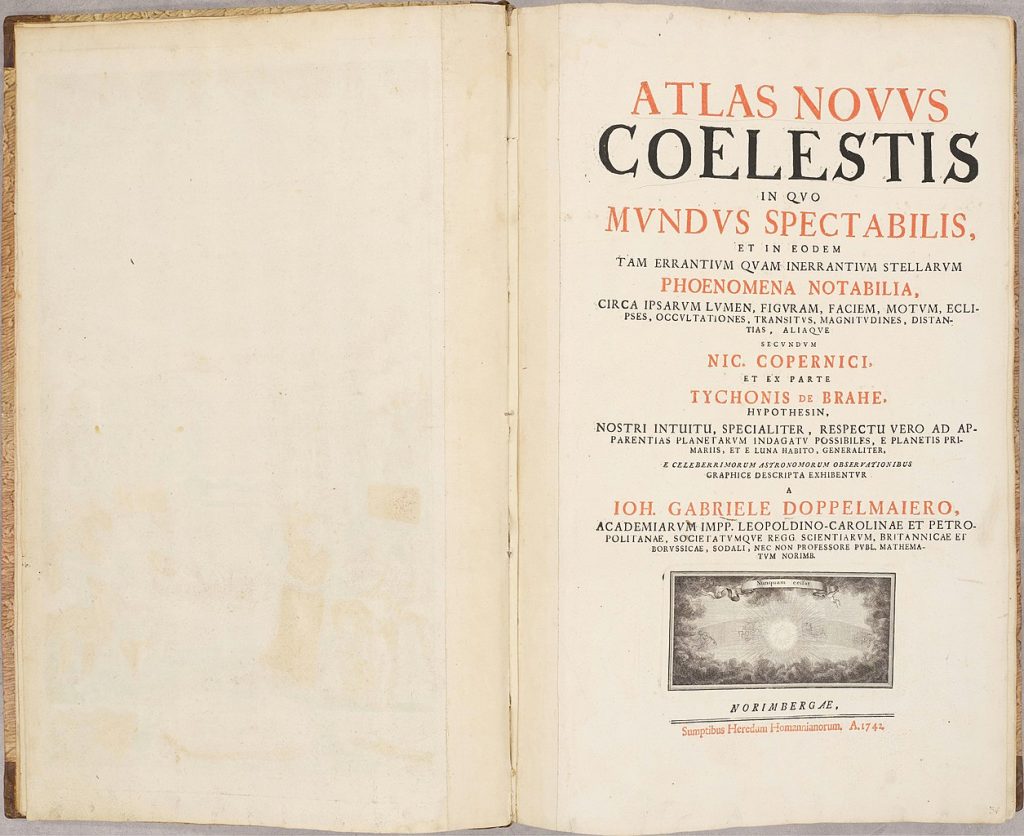

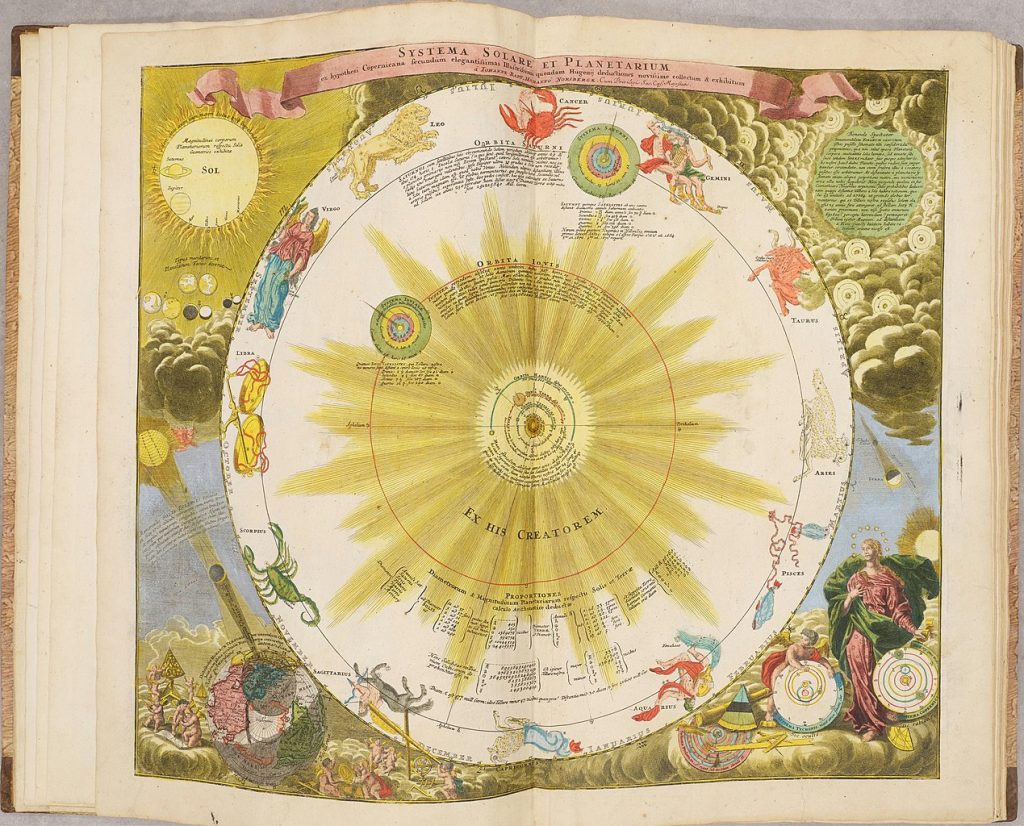

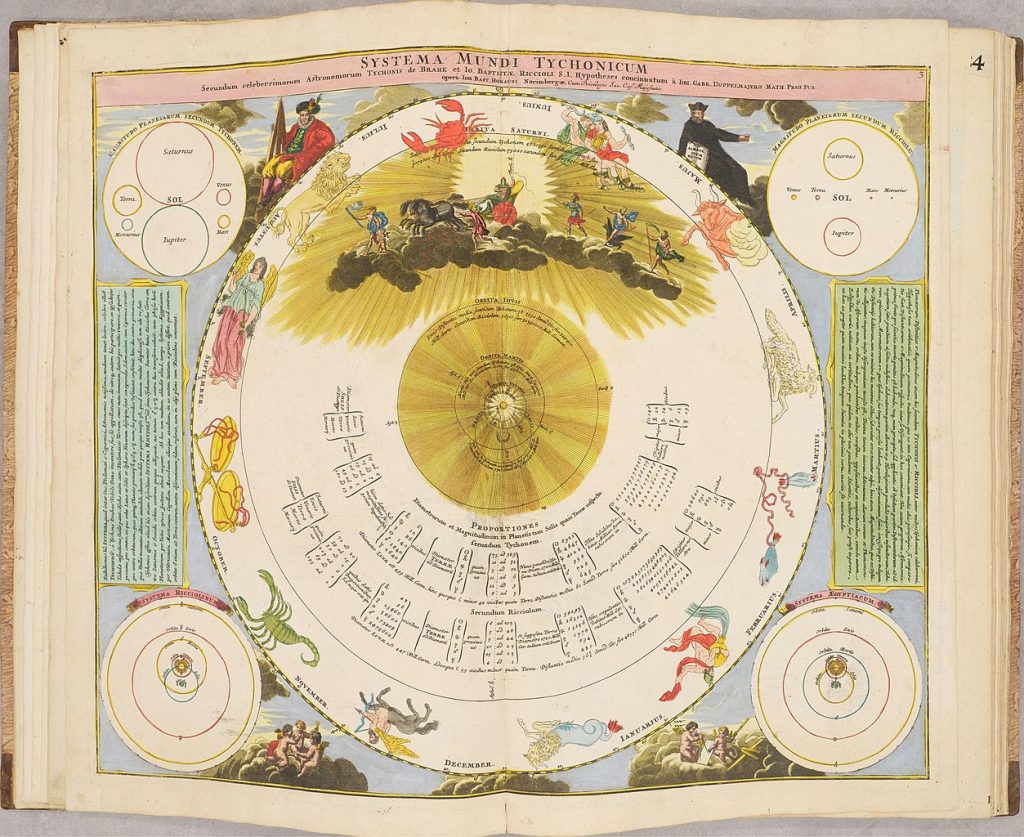

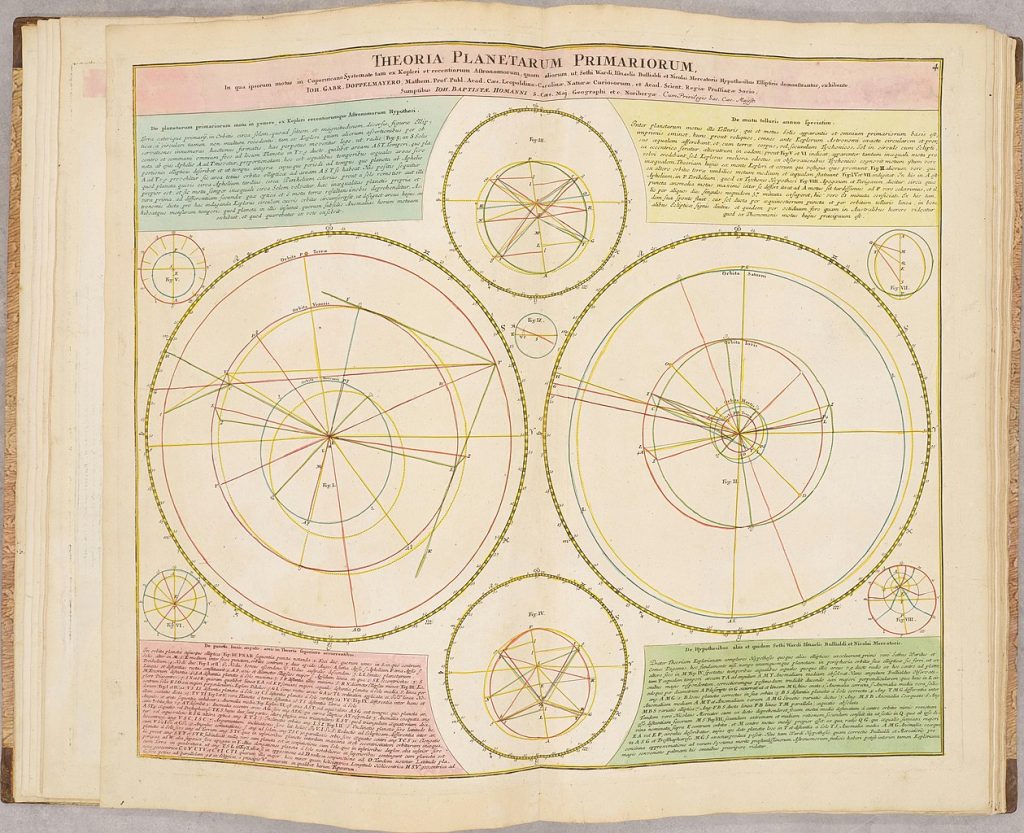

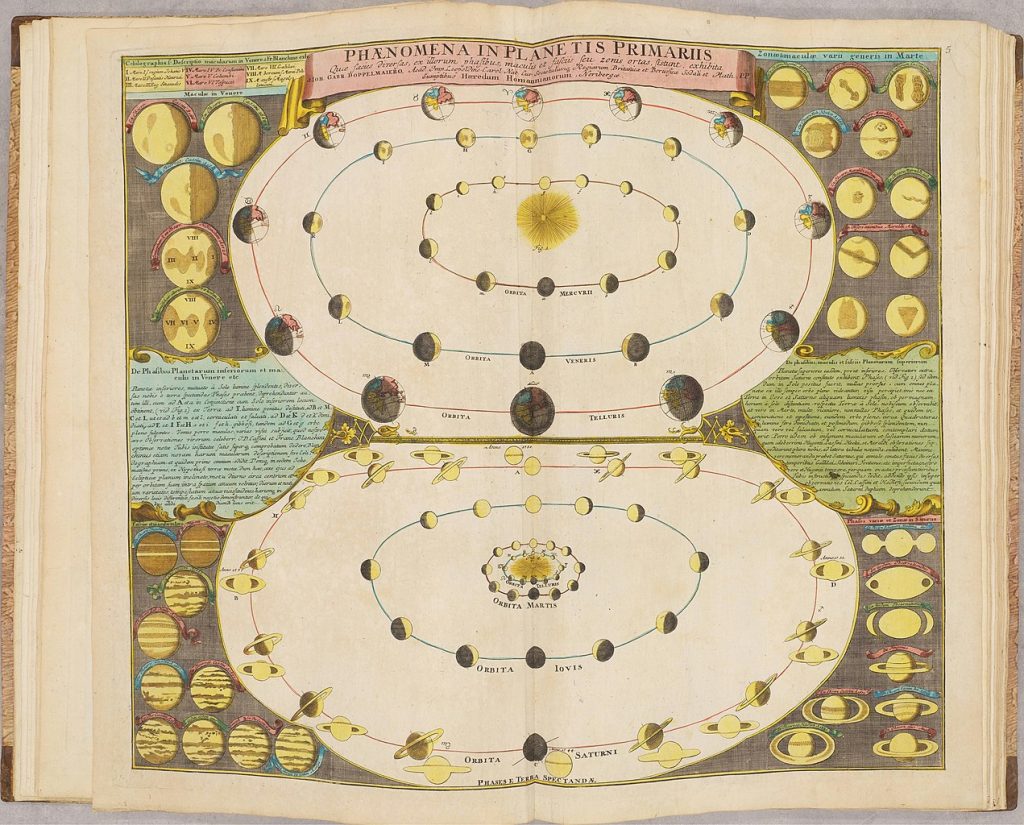

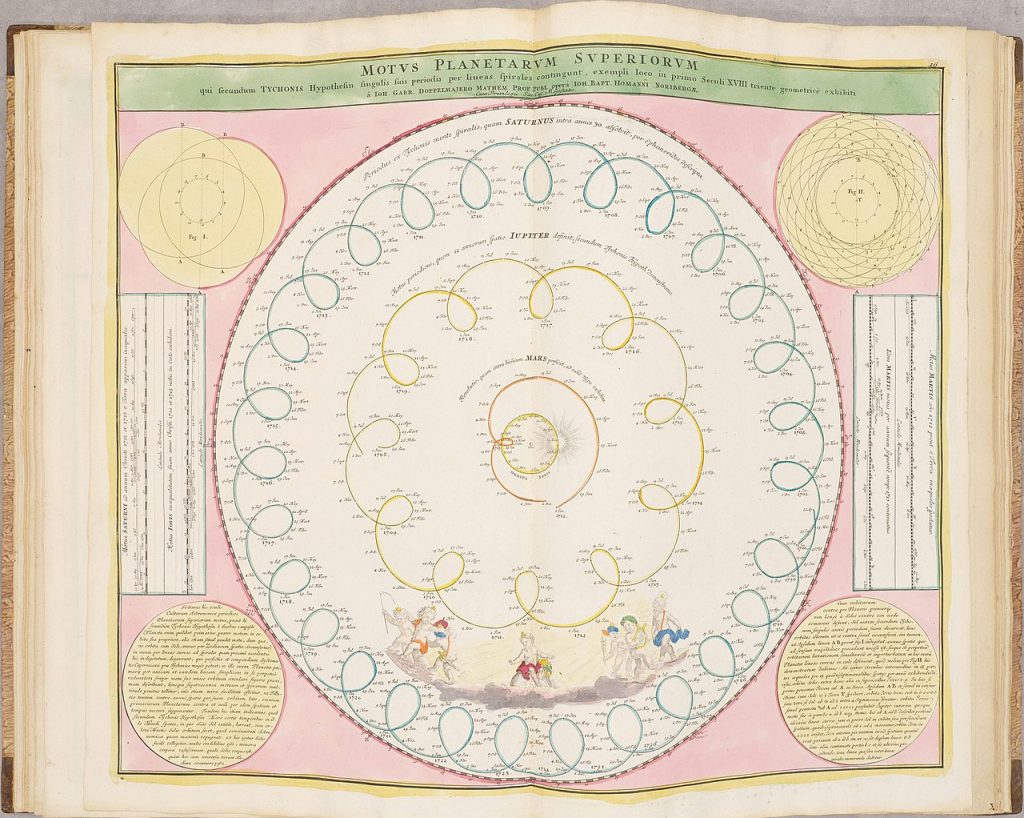

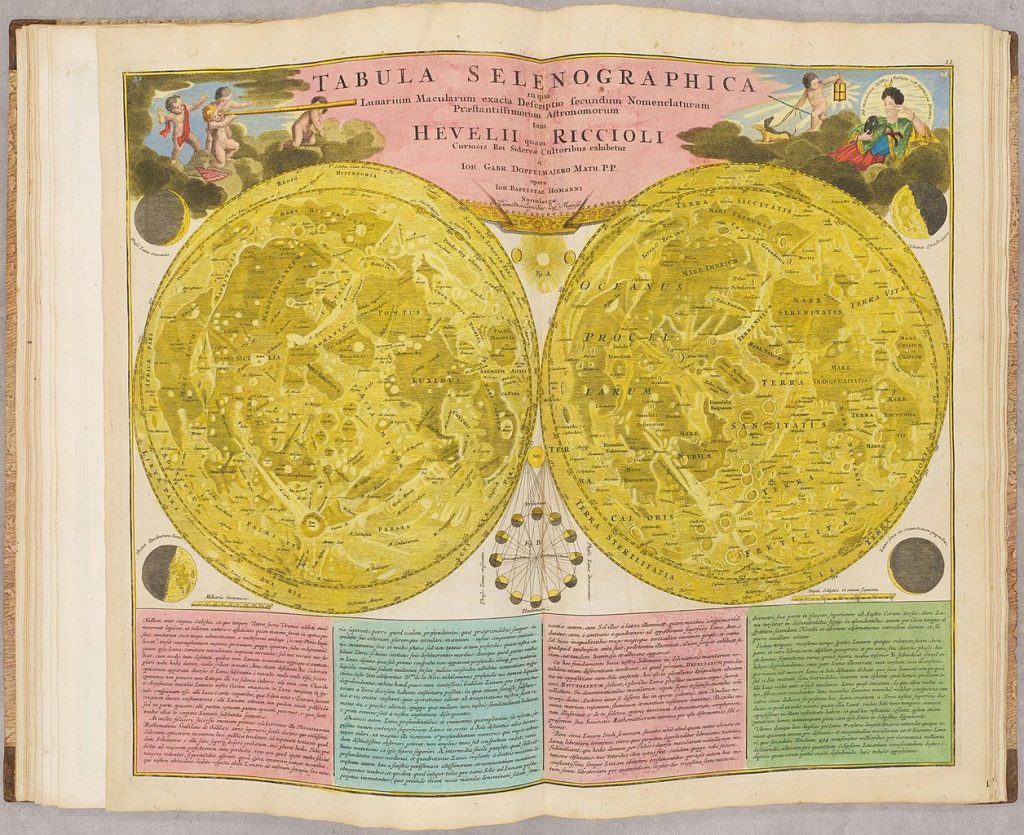

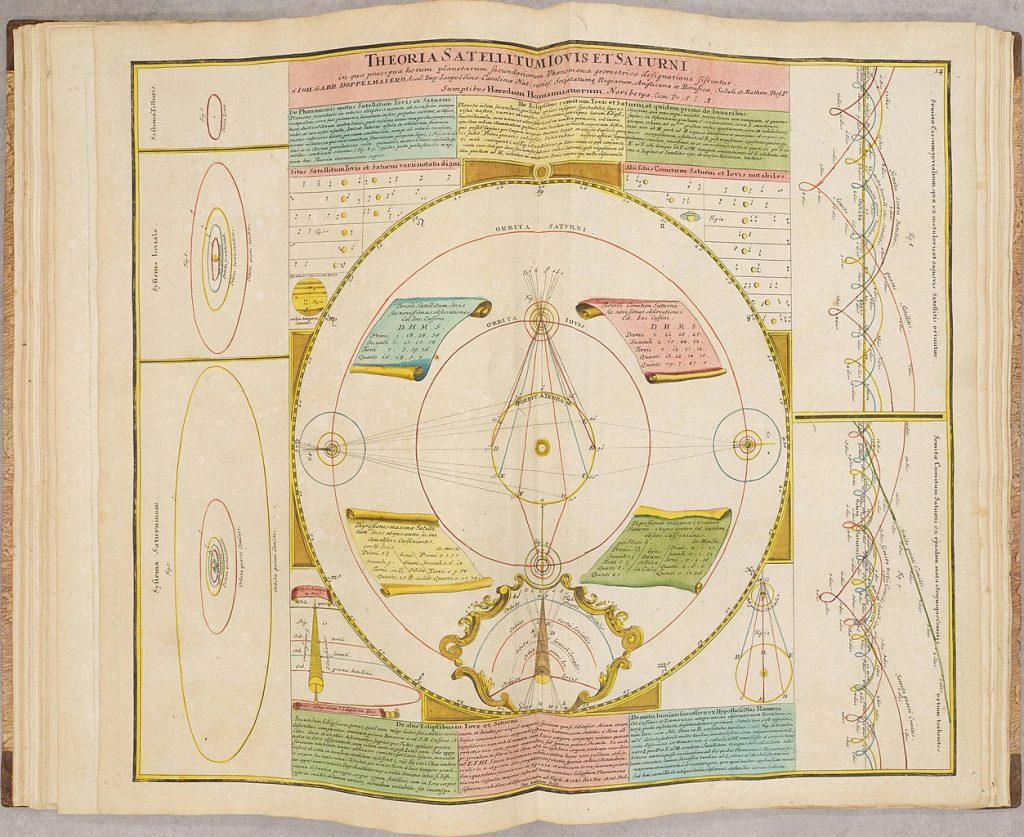

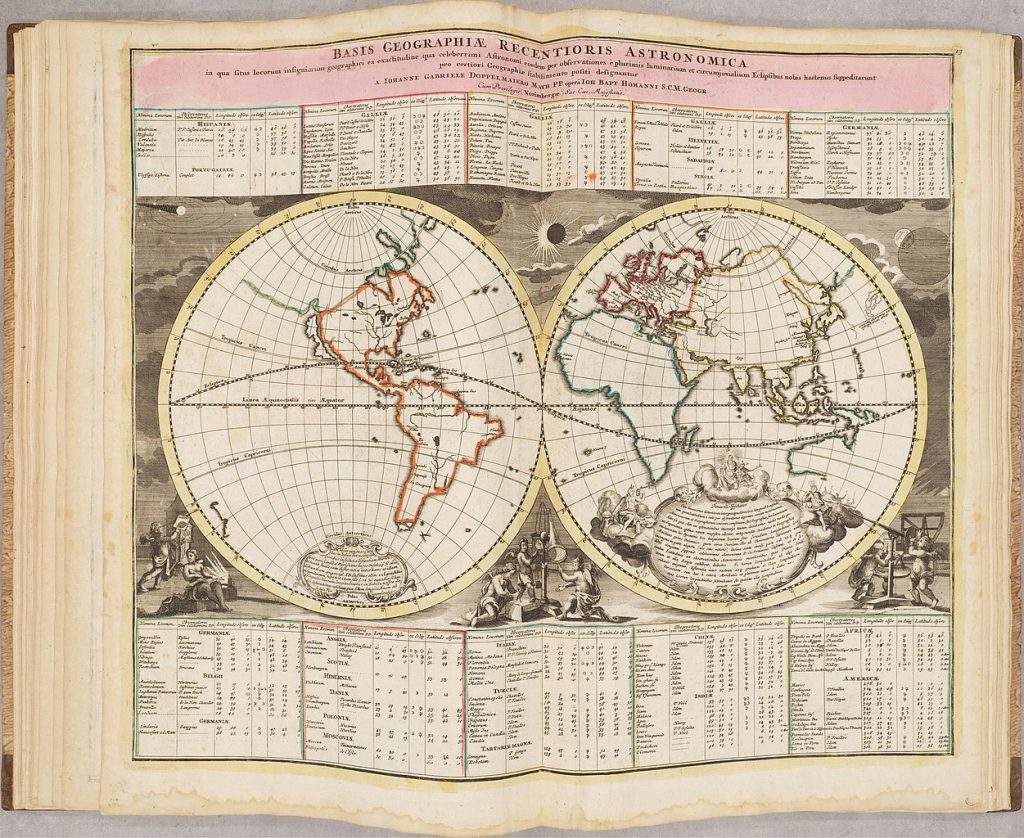

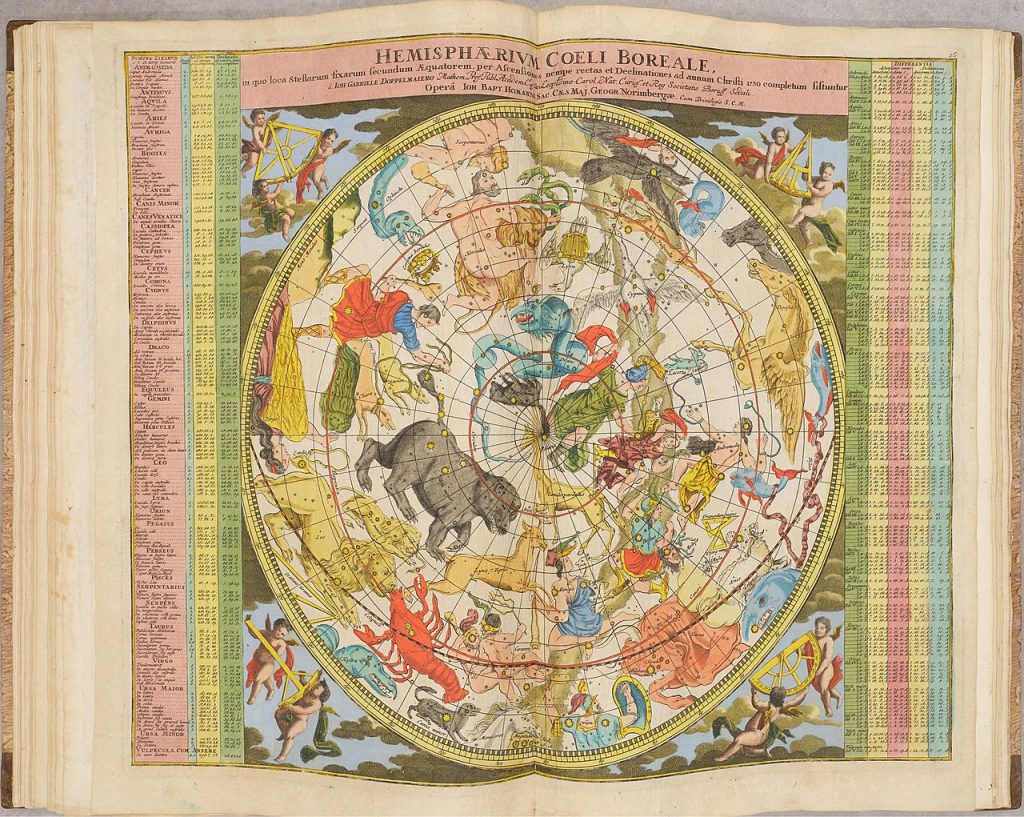

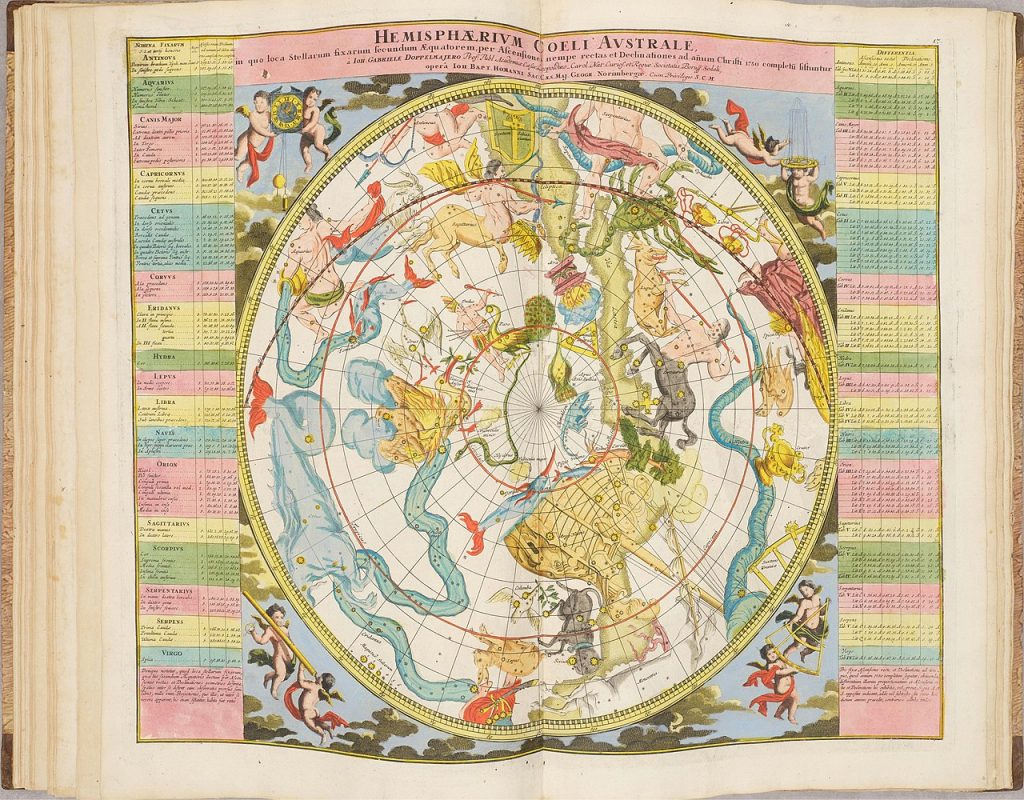

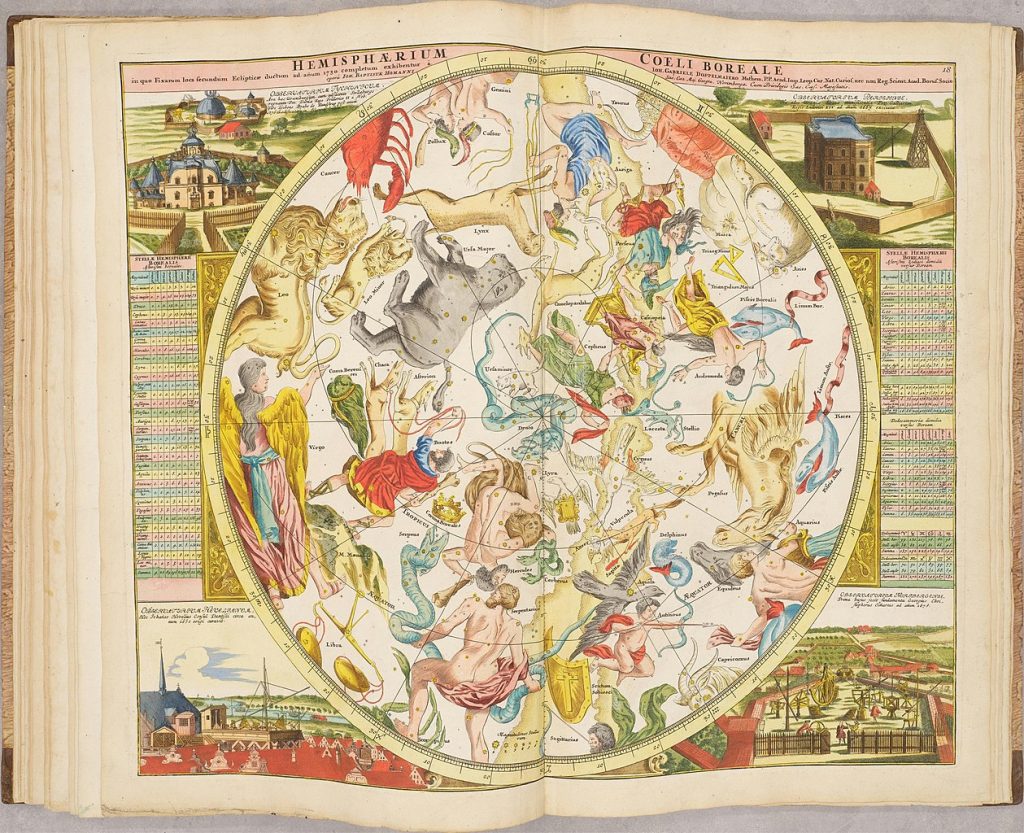

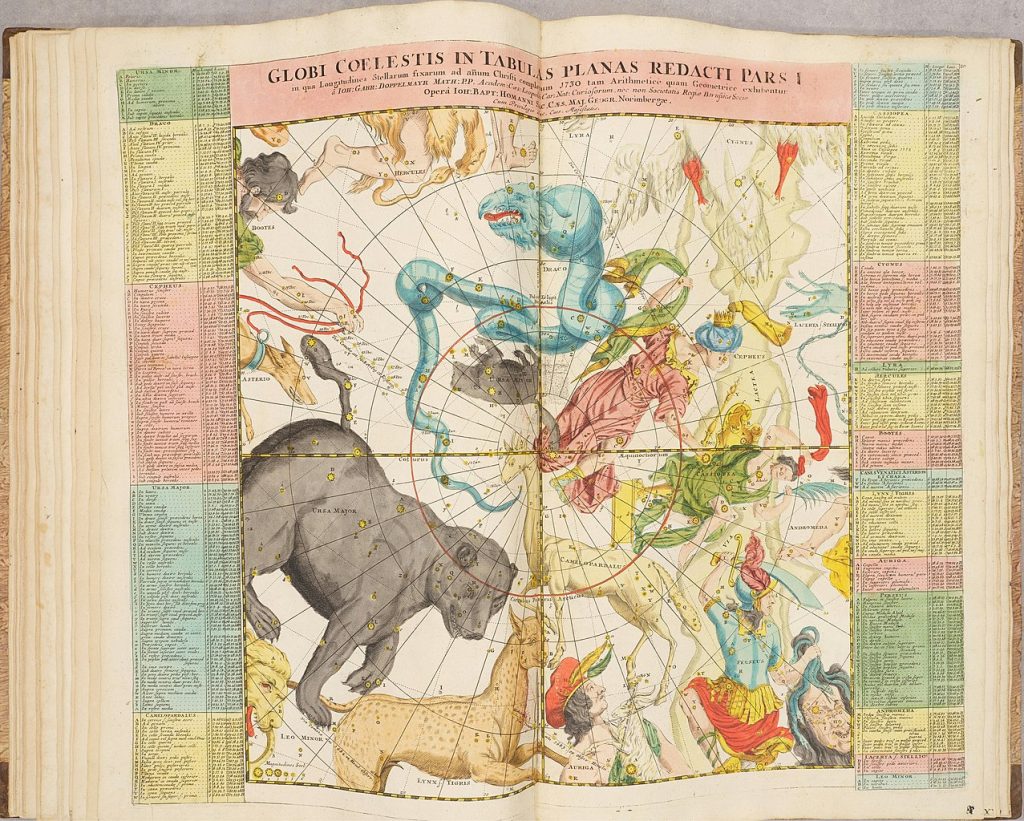

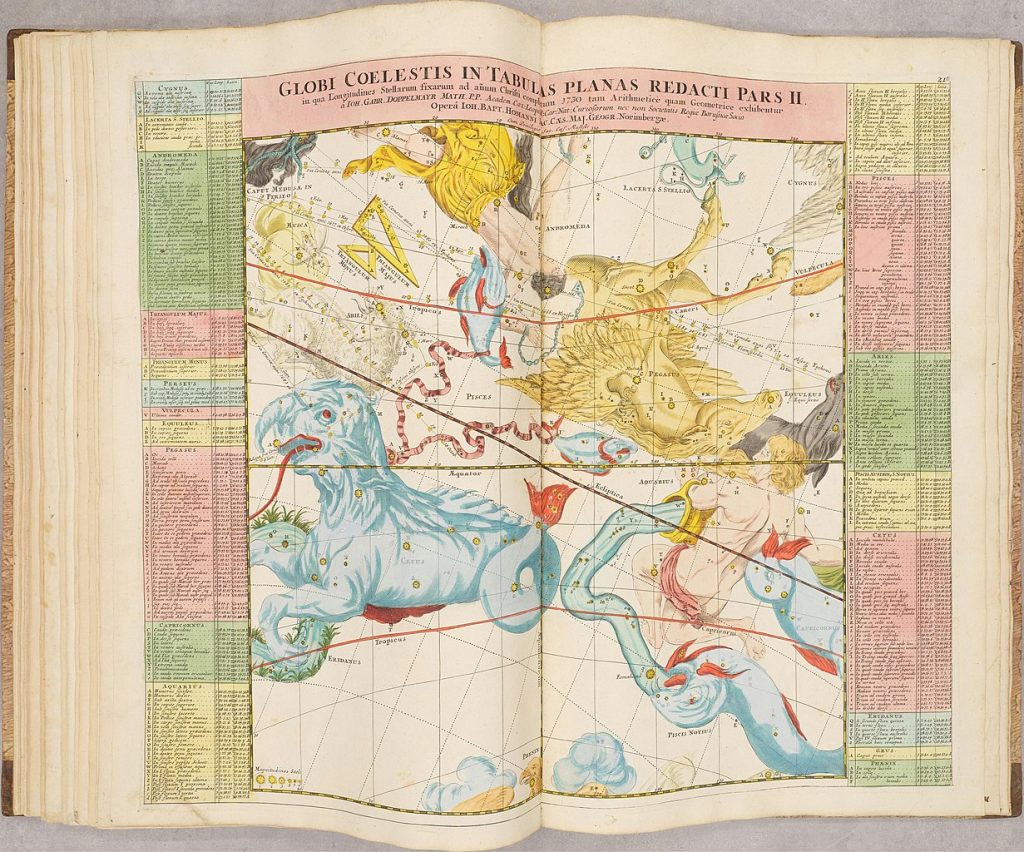

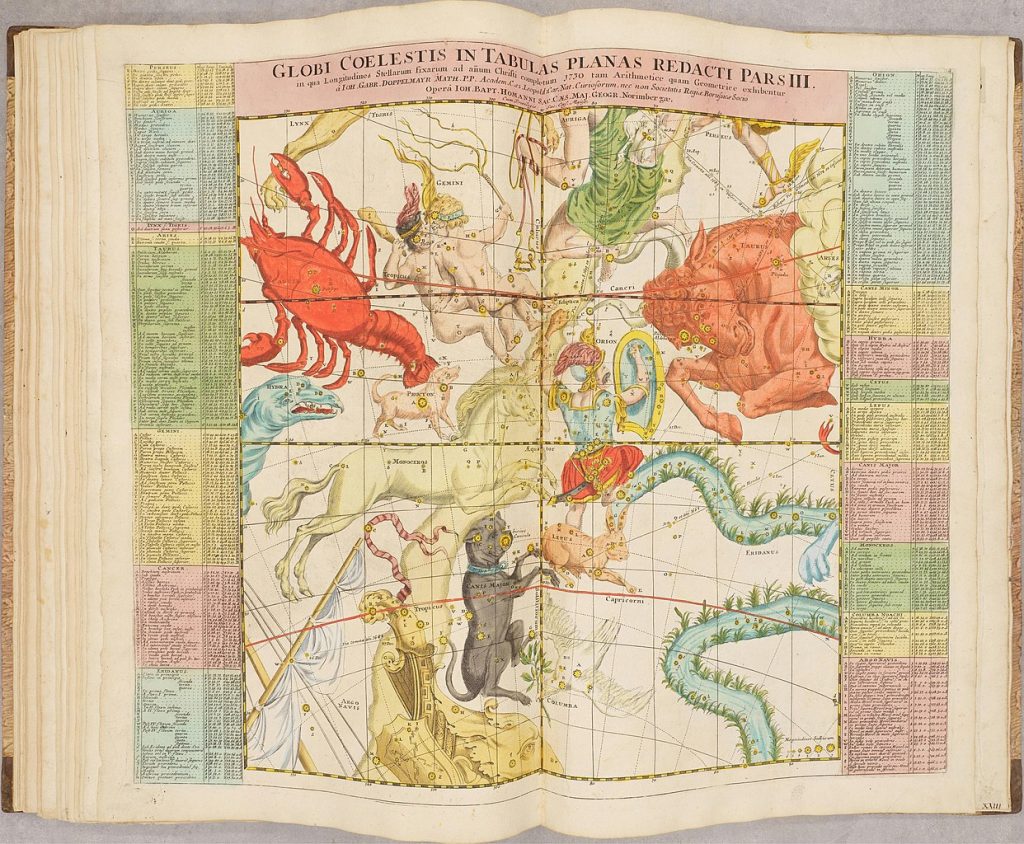

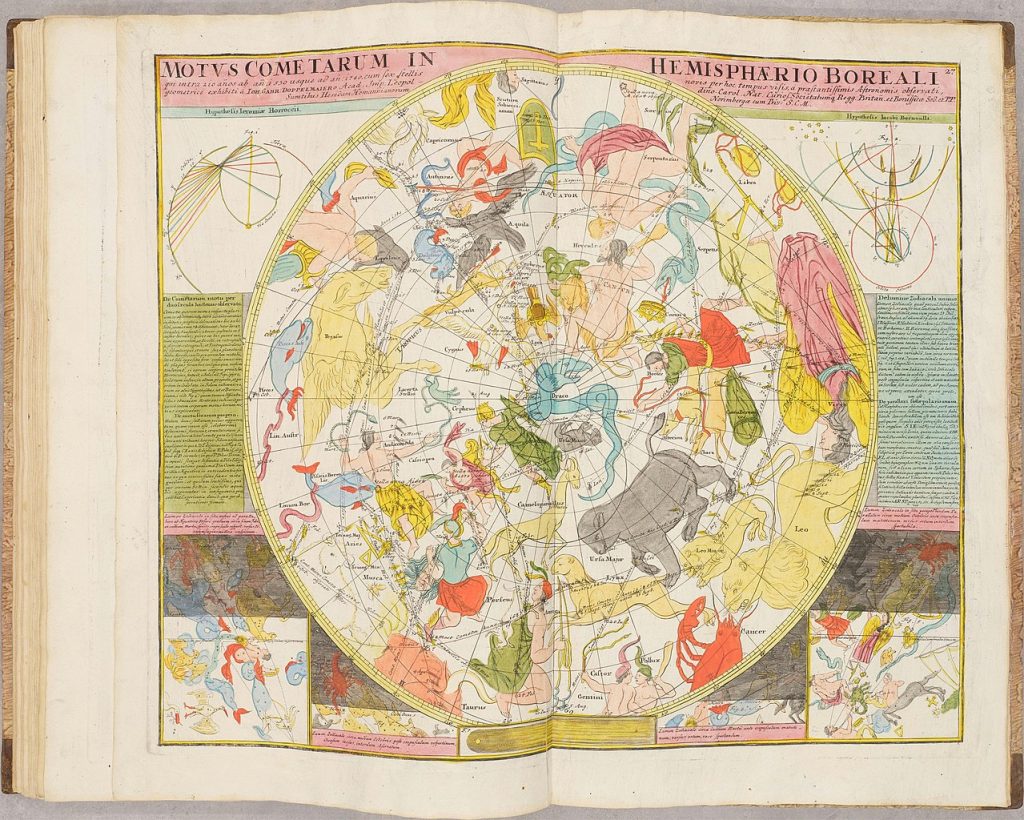

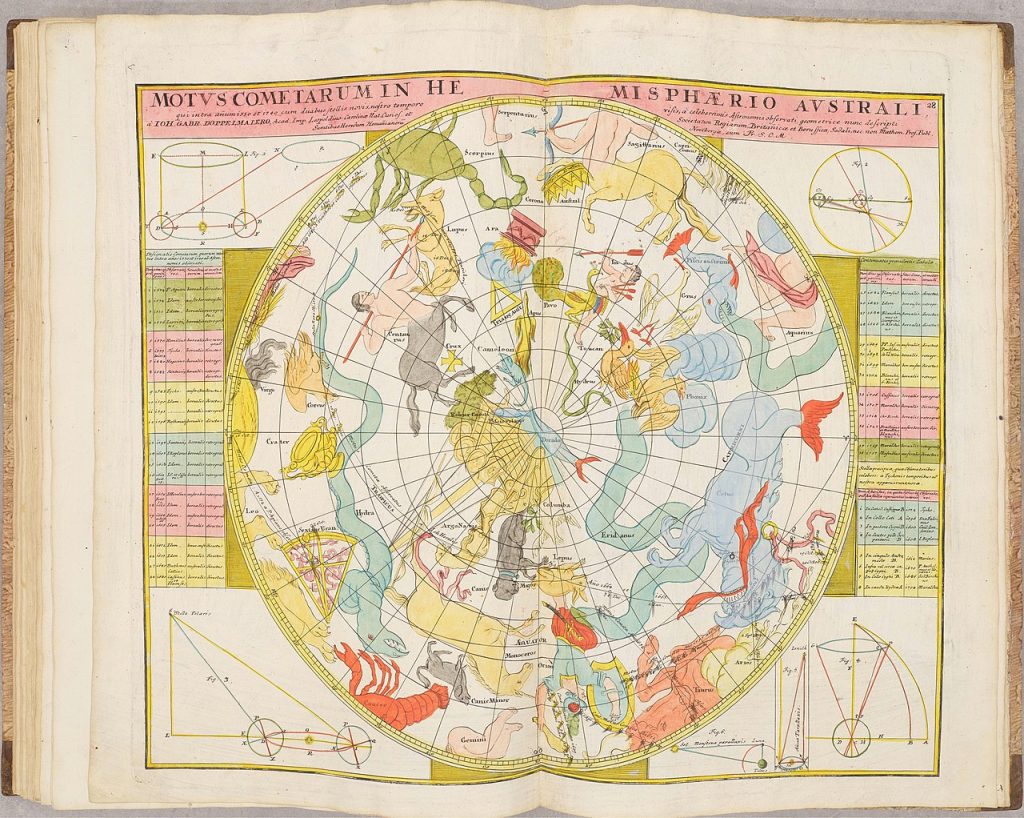

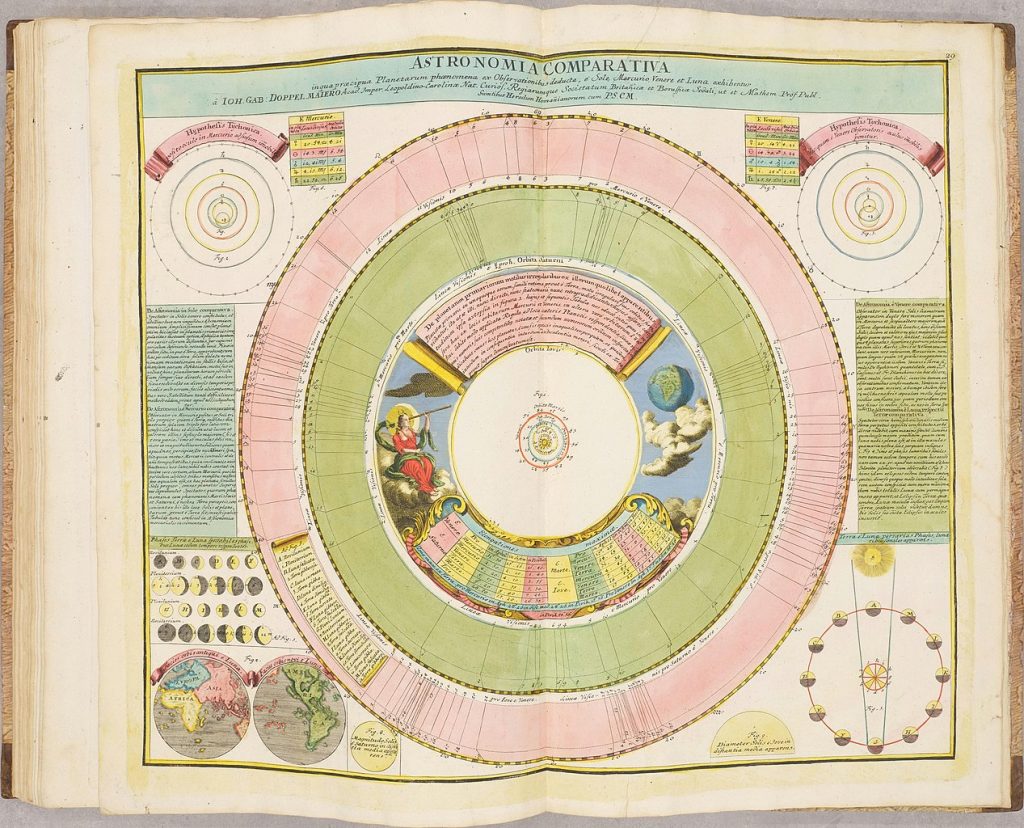

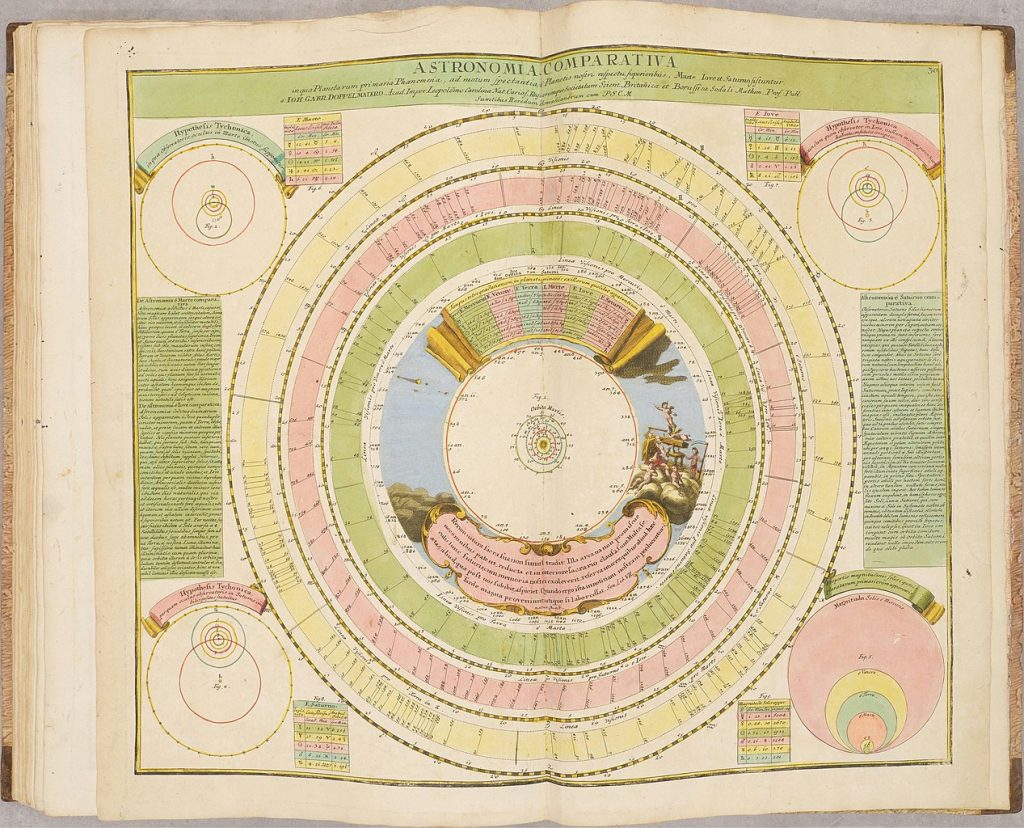

Een van zijn publicaties bevatte biografische gegevens over verschillende wiskundigen en instrumentbouwers in Nürnberg. In 1742 werkte hij de Atlas Coelestis af van de monnik Johann Batiste Homann, een van zijn medewerkers.

Hij trouwde met Susanna Maria Kellner in 1716 en kreeg vier kinderen. Hij was lid van meerdere wetenschappelijke organisaties, waaronder de Berlin Academy, de Royal Society in 1733 en de Petersburg Academy of Sciences in 1740.

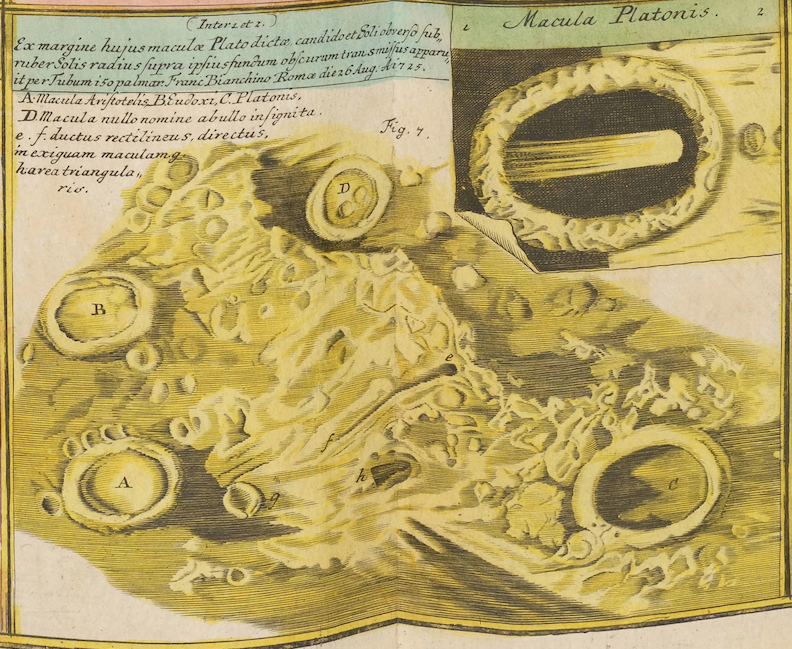

De krater Doppelmayer op de maan is naar hem genoemd door Johann Hieronymus Schröter in 1791. Ook de kleine planeet 12622 Doppelmayr kreeg zijn naam.

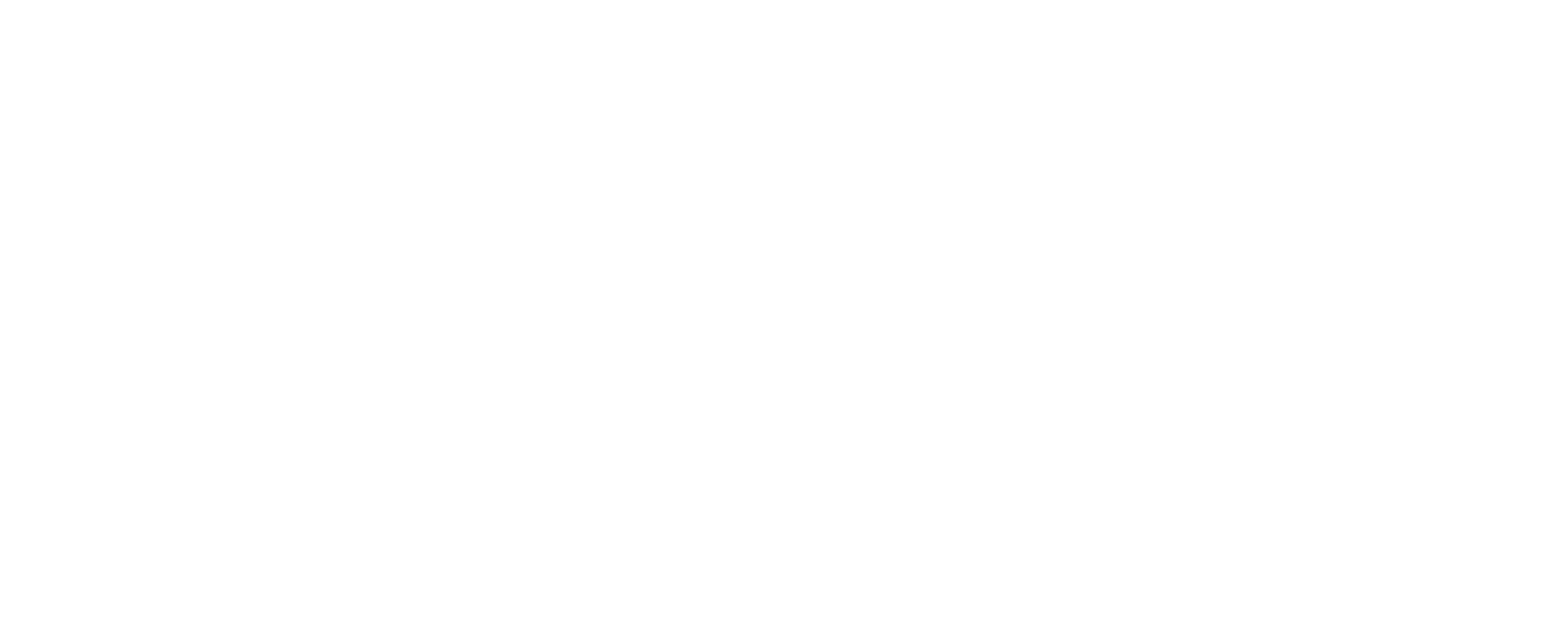

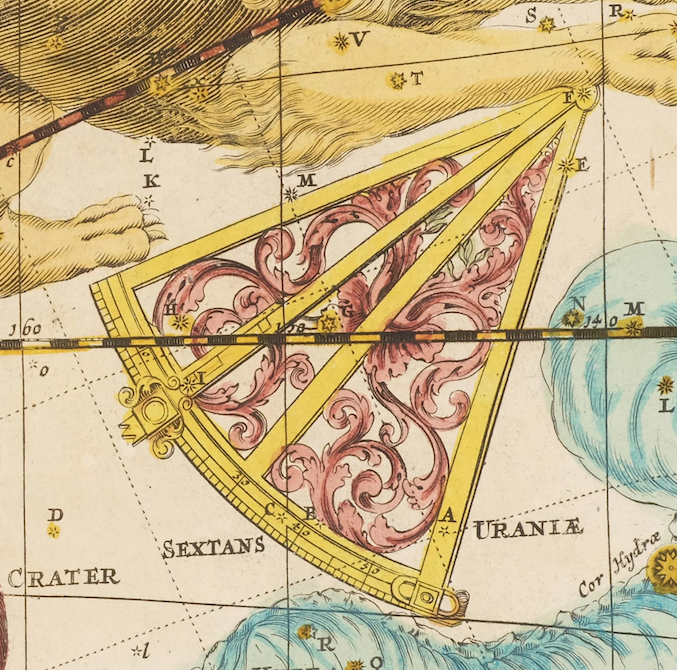

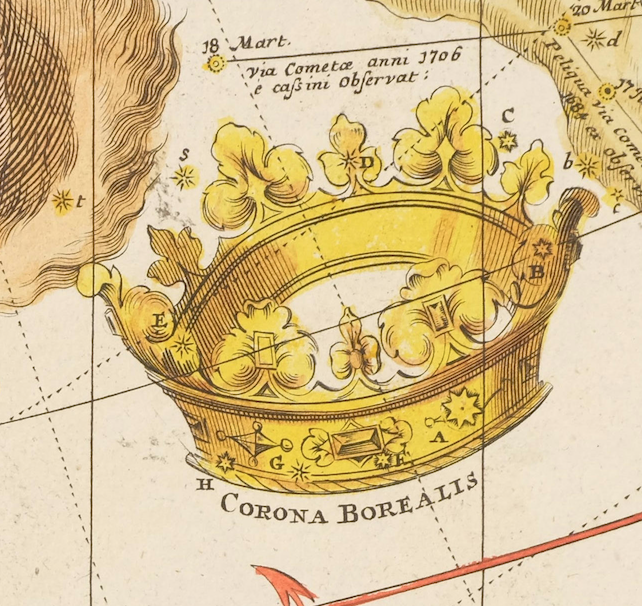

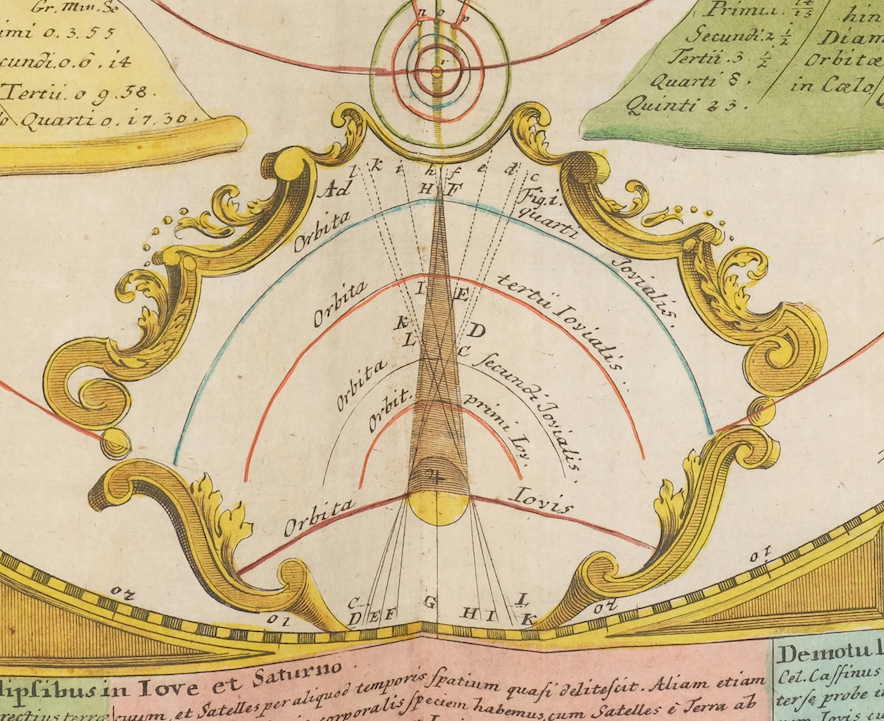

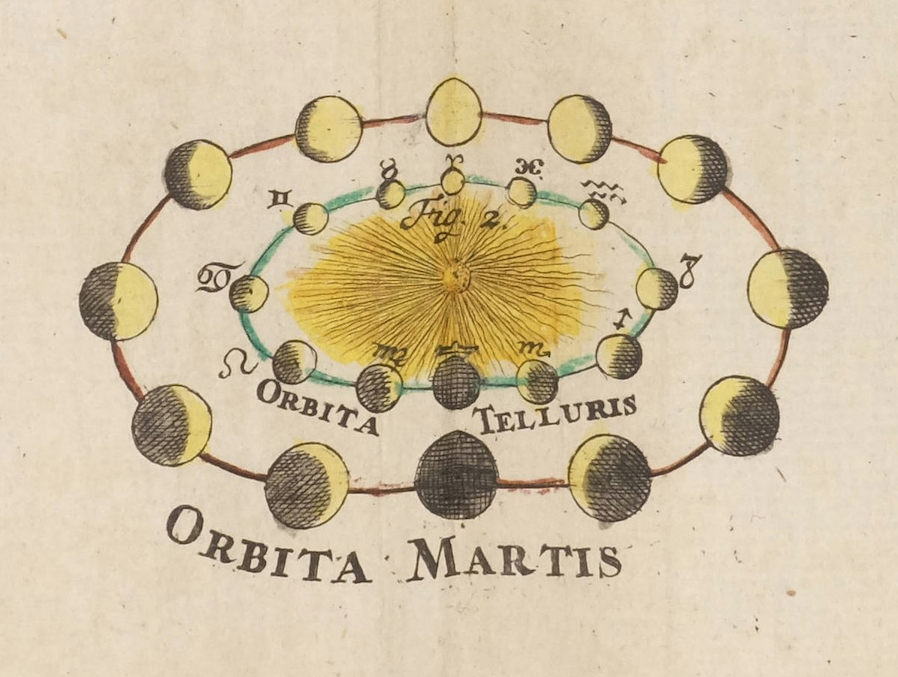

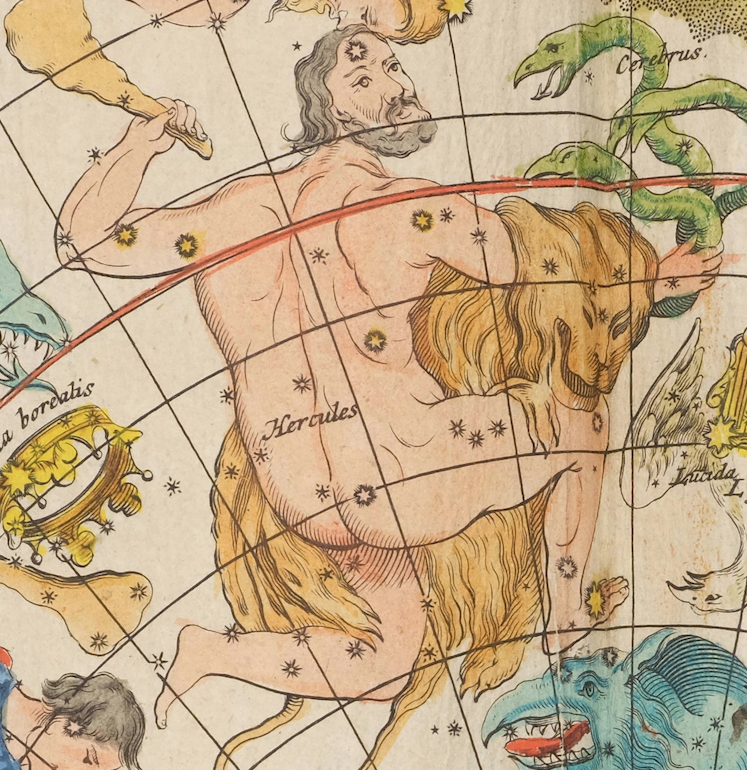

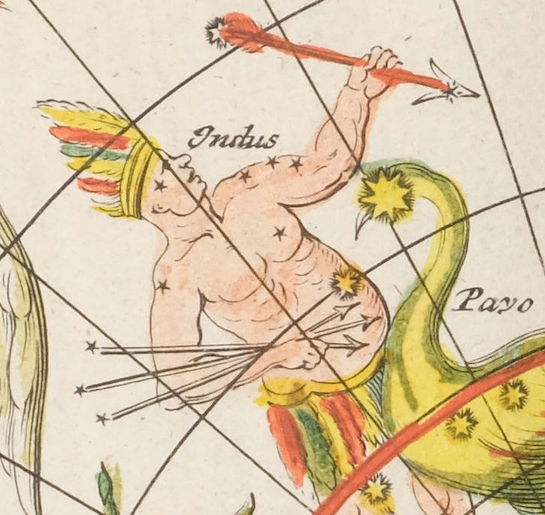

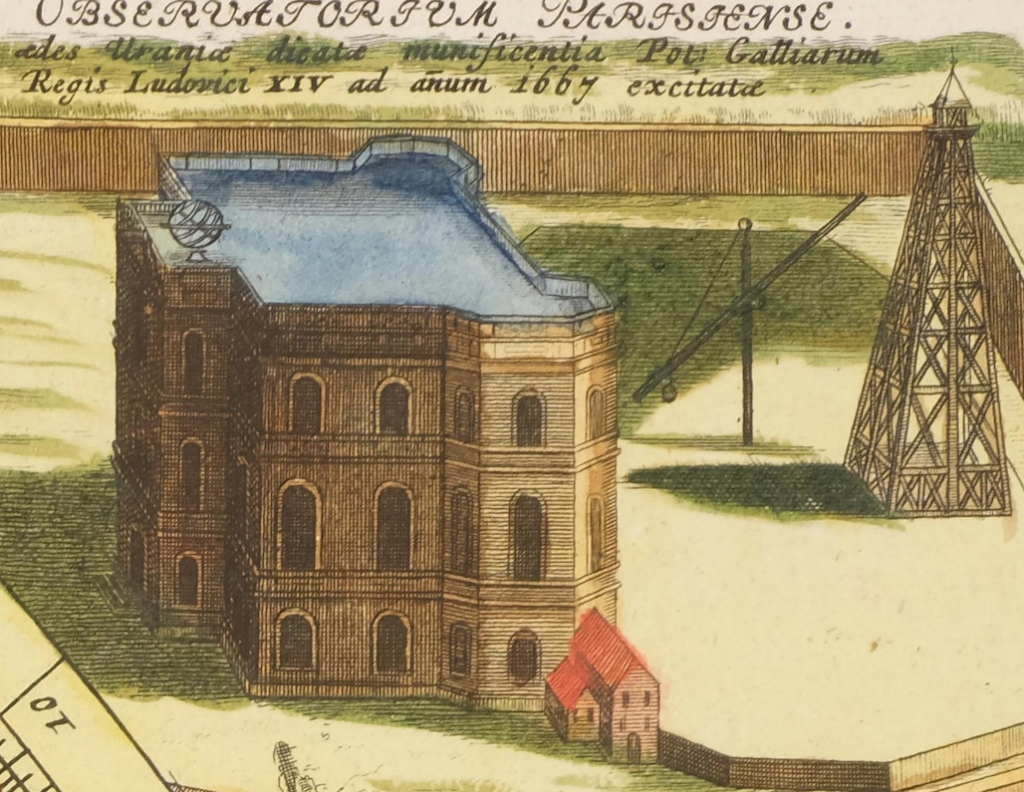

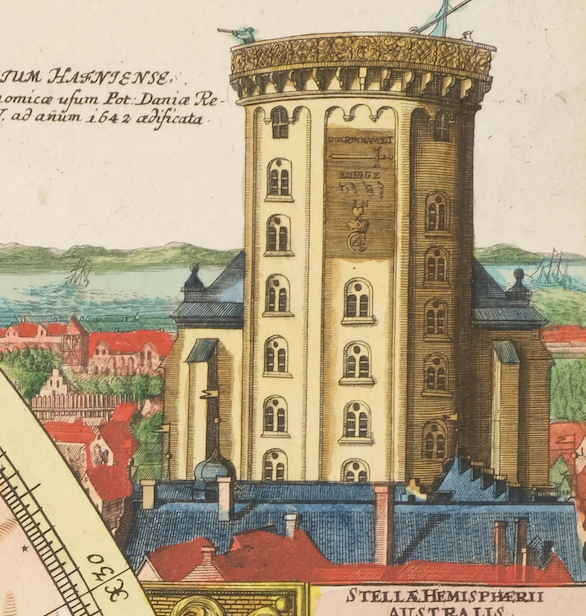

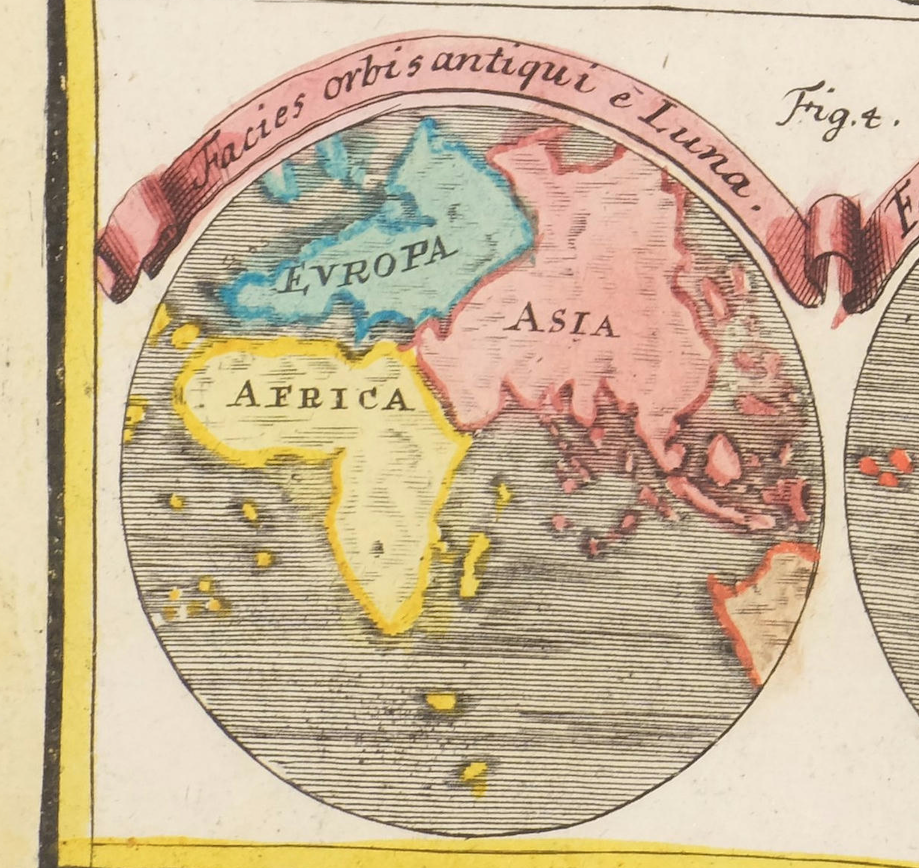

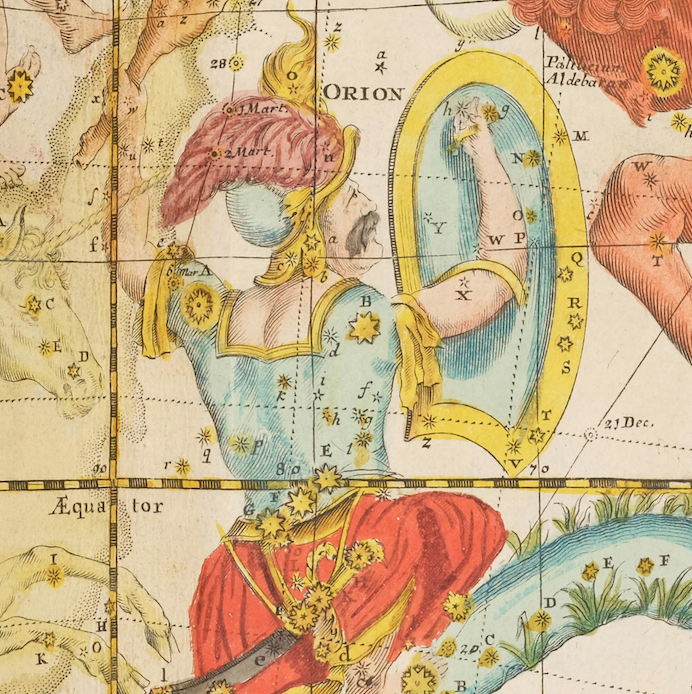

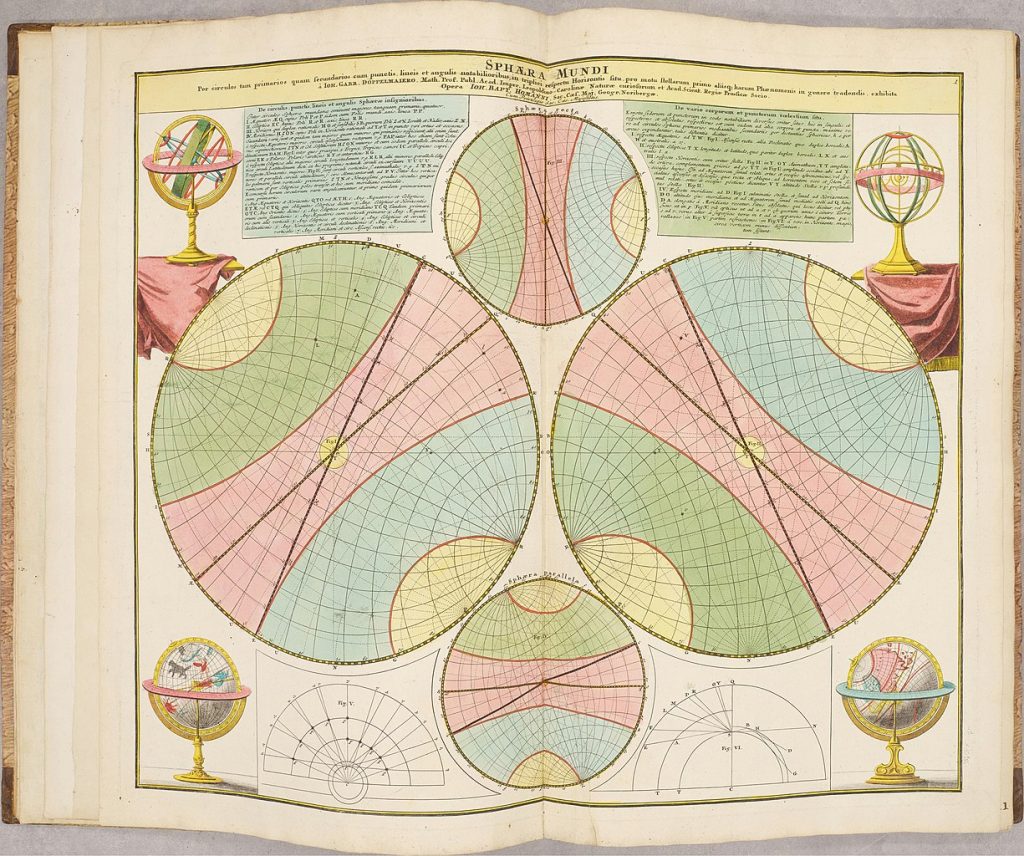

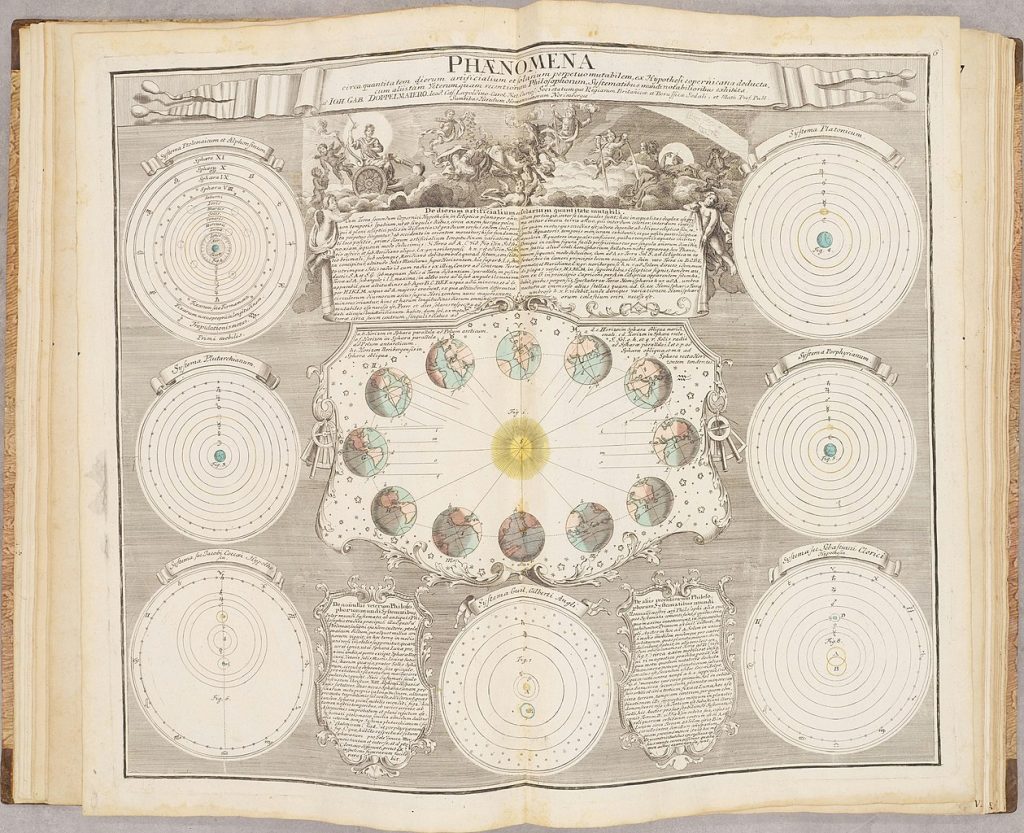

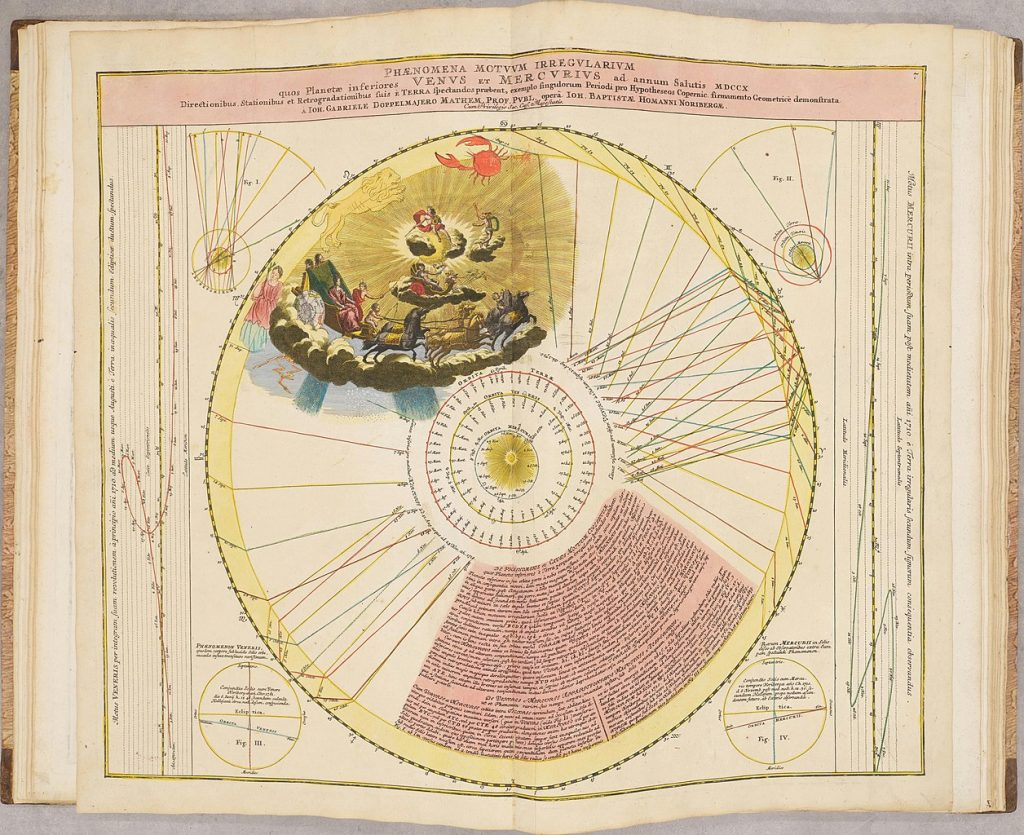

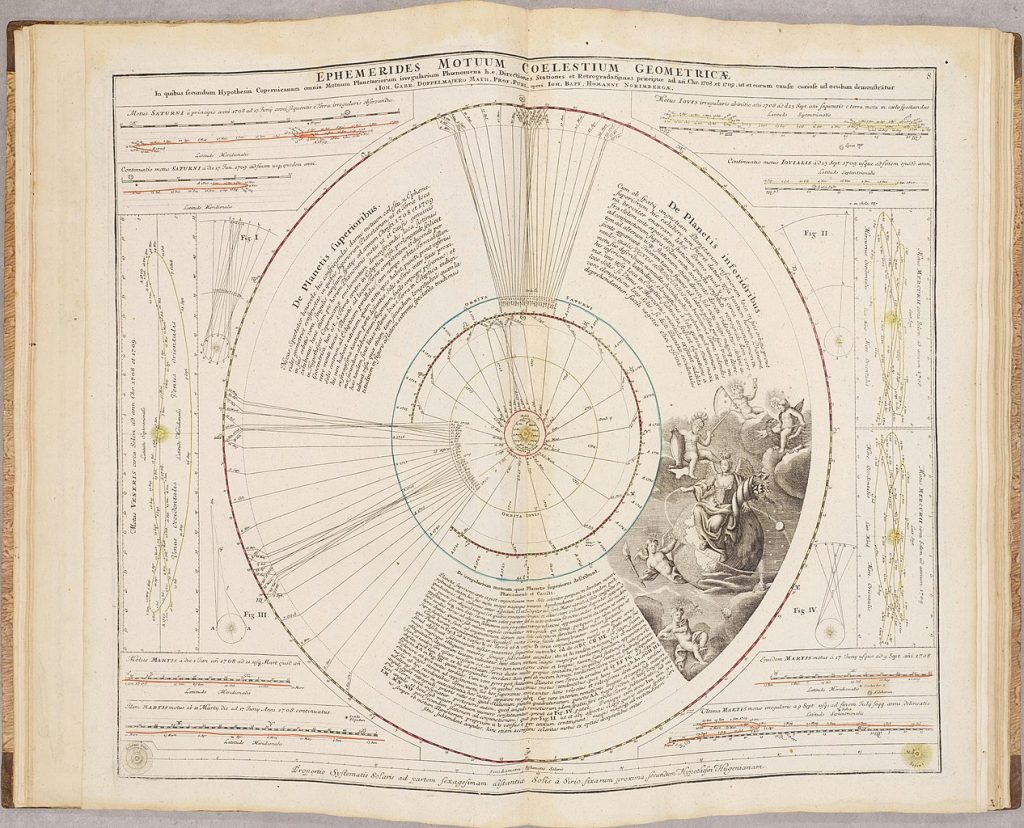

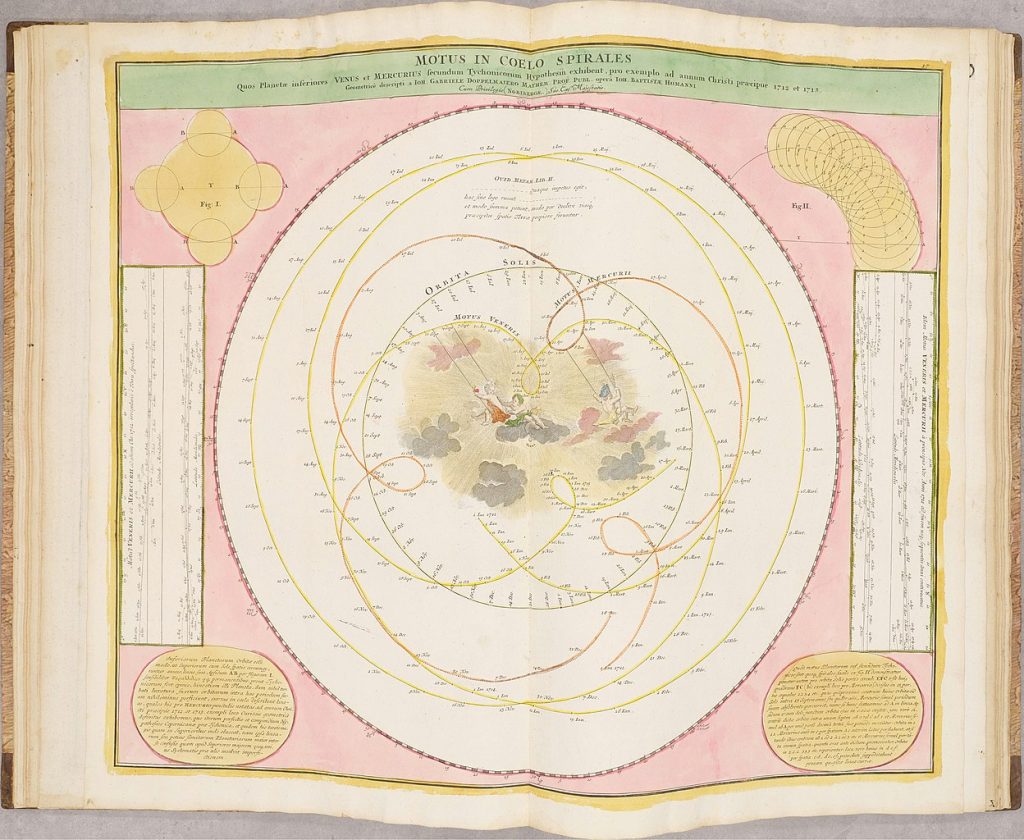

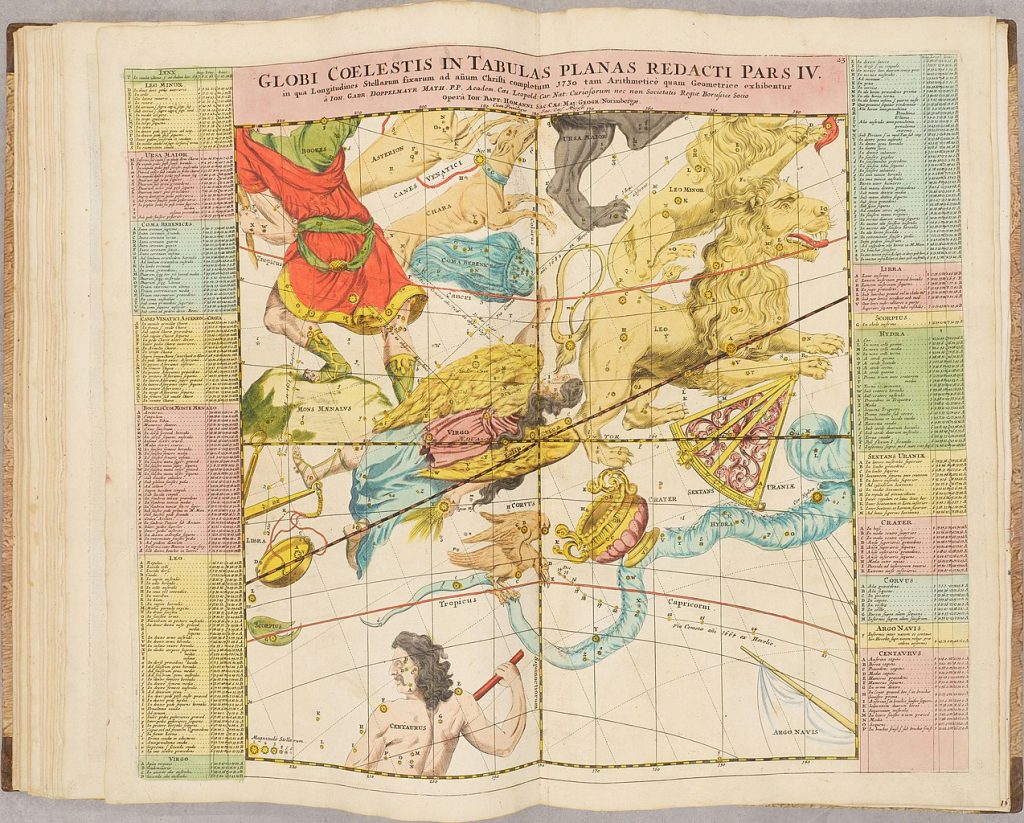

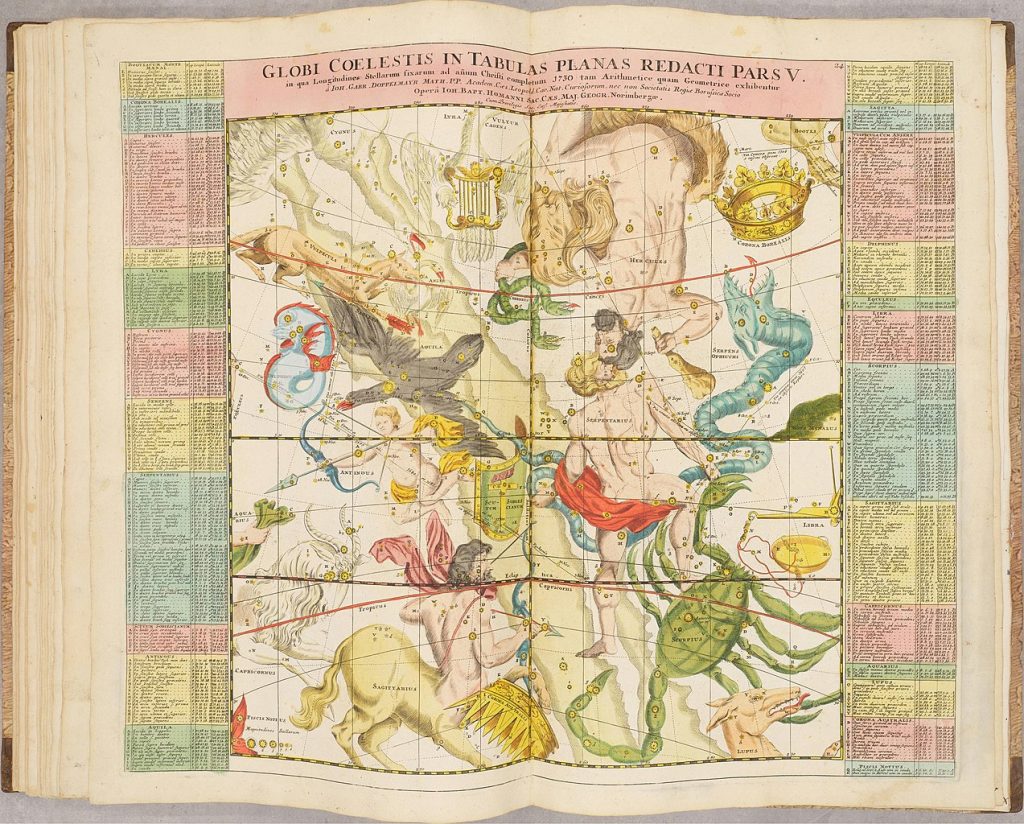

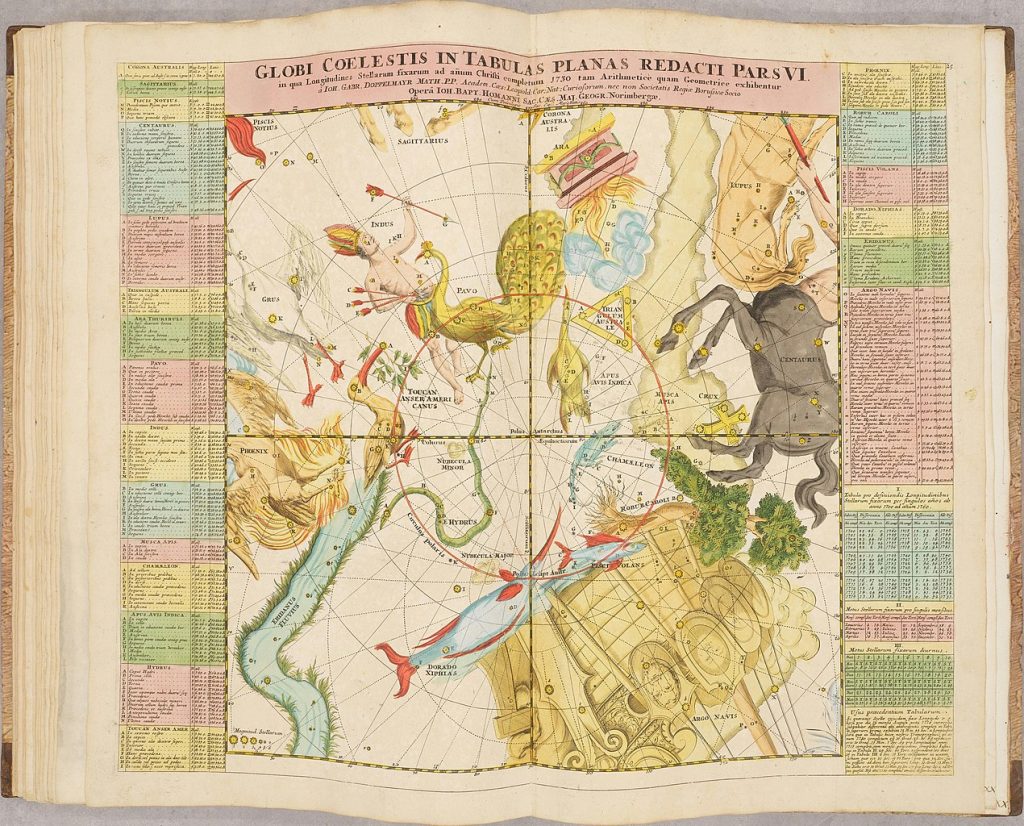

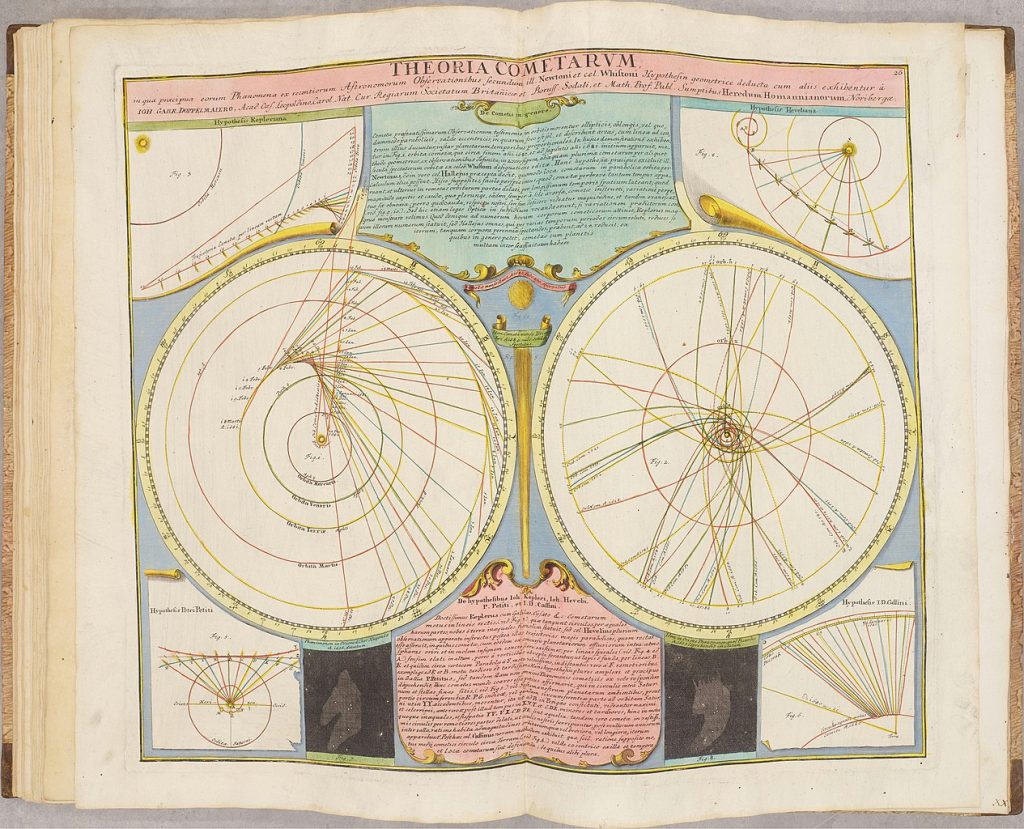

Hieronder alle platen, op volgorde van die beroemde Atlas van de Hemel (Atlas Coelestis):

Brief Biography of Johann Gabriel Doppelmayr

Bron: https://webspace.science.uu.nl/~gent0113/doppelmayr/doppelmayr.htm

Johann Gabriel Doppelmayr (also spelled Doppelmair, Doppelmaier or Doppelmayer) was the son of the Nuremberg merchant Johann Siegmund Doppelmayr (1641-1686) and was born on 29 September 1677 (many early sources incorrectly give his year of birth as 1671). His father had an interest in applied physics and was one of the first to design a vertical vacuum air pump in Nuremberg.

Doppelmayr enrolled at the Ägidiengymnasium in 1689 and after completing his studies in 1696 enrolled at the nearby university of Altdorf to study law which he completed in 1698 with a dissertation on the Sun. He then attended lectures on mathematics and natural philosophy by Johann Christoph Sturm (1635-1703) which he completed in 1699 with his dissertation De visionis sensu nobilissimo, ex camerae obscurae tenebris illustrato. He continued his studies on physics and mathematics at the university of Halle where he also learned French and Italian.

In September 1700, Doppelmayr travelled to Berlin and from there, through Lower Saxony, to Holland where he visited Franeker and Amsterdam on his way to Utrecht where he stayed for a couple of months to continue his studies on physics and mathematics and to master the English language.

In April 1701, Doppelmayr went to Leiden where he stayed in the house of the astronomy professor Lothar Zumbach von Koesfeld (1661-1727) and learned (probably in the Musschenbroek workshop) how to grind and figure telescope lenses. He then travelled to Rotterdam and in May to England where he visited Oxford and London.

After returning to Holland in the end of 1701, Doppelmayr spent another five months in Leiden, where he followed astronomy lessons from Lothar Zumbach von Koesfeld. After visiting Utrecht, Deventer, Osnabrück, Hannover, Kassel, Marburg, Gießen, Wetzlar and Frankfurt, Doppelmayr returned to Nuremberg in August 1702 and was appointed professor of mathematics at the Ägidiengymnasium in 1704, a position that he would hold until his death.

In February 1716, Doppelmayr married Susanna Maria Kellner (1697-1728) with who he had four children (three of whom died shortly after their birth).

In 1723, he received an invitation to become the professor of mechanics at the Academy of St. Petersburg, but Doppelmayr declined and suggested that they should ask the Swiss mathematician Nikolaus Bernouilli for this position.

Doppelmayr wrote on astronomy, geography, cartography, spherical trigonometry, sundials and mathematical instruments. He often collaborated with the cartographer Johann Baptist Homann (1664-1724), a former Dominican monk from Oberkammlach in Schwabia who in 1688 had settled in Nuremberg and became a map engraver for the publishing firms of Jacob von Sandrart (1630-1708) and David Funck (1642-1709). In 1702, Homann founded an influential cartographic publishing firm that after his death was continued by his son Johann Christoph Homann (1703-1730) and after the latter’s death by his friend Johann Michael Franz (1700-1761) and his stepsister’s husband Johann Georg Ebersberger (1695-1760) under the name “Homännische Erben”. The publishing firm remained in business under different names until 1848.

Among Doppelmayr’s many students was Georg Friedrich Brander (1713-1783) from Regensburg, who settled in Augsburg in 1734 and in 1737 founded a renowned workshop for scientific instruments.

Doppelmayr was elected as a member of several scientific societies, including the Berlin Academy of Sciences, the Kaiserlich Leopoldinische Akademie der Naturforscher in Halle (1715), the Royal Society of London (on 6 December 1733, not in 1713 as mentioned in several sources) and the St. Petersburg Academy of Sciences (1740).

Doppelmayr died on 1 December 1750 in Nuremberg, and many later sources claim that his death was caused by the fatal effects of a powerful electrical shock which he had received shortly before while experimenting with a battery of electric capacitors. Other sources, however, suggest that Doppelmayr’s electrical experiments were performed several years earlier and were not the cause of his death.

The lunar crater Doppelmayer (latitude 28.5° south and longitude 41.4° west), the nearby rille Rimae Doppelmayer (latitude 25.9° south and longitude 45.1° west) and the minor planet 12622 Doppelmayr are named in his honour.

Doppelmayr’s astronomical publications

Doppelmayr was responsible for the edition and translation of several important works in astronomy, geography and scientific instrument making.

- 17?? – German translation of Sanson’s Introduction à la Géographie (Paris, 1699).

- 17?? – German translation of the L’usage des globes célestes et terrestres, et des sphéres (Paris, 1699) by Nicholas Bion.

- 1705 – Astronomia Carolina, Nova Theoria Motuum Coelestium, secundum optimas Observationes & rationi maxime consentanea fundamenta Artis […] cum exactis & facillimis ad hanc Tabulis & Praeceptis pro calculo Eclipsium &c. [e-rara link] – Latin translation of the Astronomia Carolina: A New Theorie of the Cœlestial Motions (London, 1665) of Thomas Streete.

- 1708 – Neu-vermehrte Welperische Gnomonica oder gründlicher Unterricht und Beschreibung wie man alle regulare Sonnen-Uhren auf ebenen Orten leichtlich aufreissen – an expanded version of a treatise on sundials first published by Eberhard Welper (1590-1664) in 1625 (with subsequent additions by Johann Christoph Sturm in 1672 and 1681) to which Doppelmayr added a German translation of William Durham’s The Artificial Clock-Maker (London, 1696) – further editions were published in 1719, 1729 and 1786.

- 1712 – Neu-eröffnete mathematische Werck-Schule Nicolai Bion – German translation of the Traité de la construction et des principaux usages des instrumens de mathématiques (Paris, 1709) by Nicolas Bion – further expanded editions were published in 1717, 1721, 1726, 1741 and 1765.

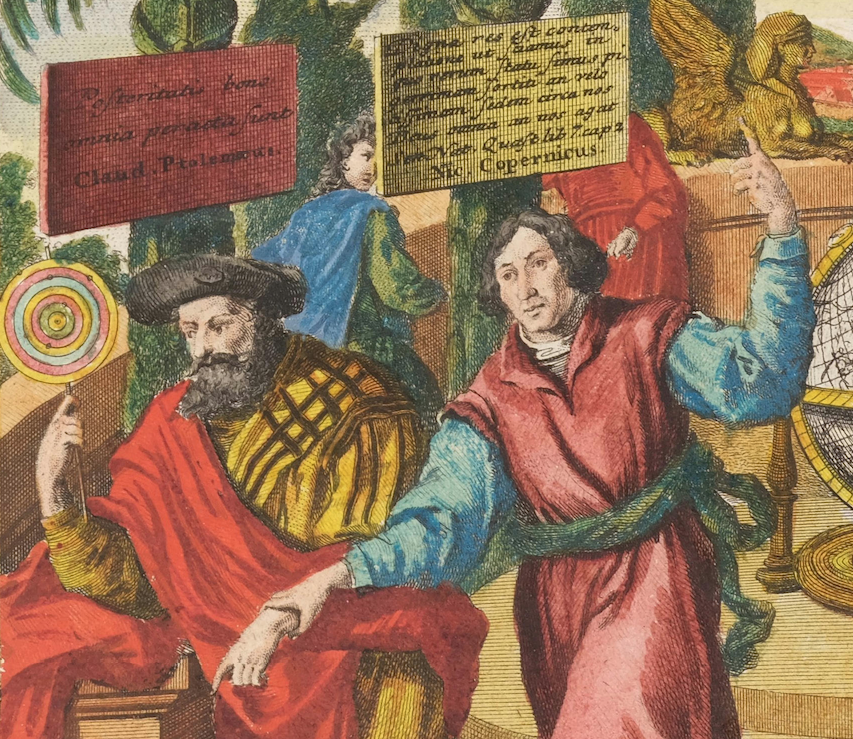

- 1713 – Johannes Wilkins, des fürtrefflichen Englischen Bischoffs zu Chester Vertheidigter Copernicus, oder Curioser und gründlicher Beweiß der Copernicanischen Grundsätze – a German translation of the Discovery of a new Worlde in the Moone(London, 1638) by John Wilkins.

- 1730 – Historische Nachricht von den Nürnbergischen Mathematicis und Künstlern, welche fast von dreyen Seculis her durch ihre Schriften und Kunst-Bemühungen die Mathematic und mehrere Künste in Nürnberg vor andern trefflich befördert und sich um solche sehr wohl verdient gemacht zu einem guten Exempel, und zur weitern rühmlichen Nachahmung [e-rara link] – biographical information on 360 mathematicians and instrument makers of Nuremberg, chronologically arranged from the 15th century to the early 18th century.

- 1731 – Physica Experimentis Illustrata : Oder Die durch viele Experimenta und Kunst-Proben beförderte Natur-Wissenschafft in einem Kurtzen-Begriff dargegeben, in den so benannten Collegiis Curiosis weiter erkläret und demonstriret [e-rara link].

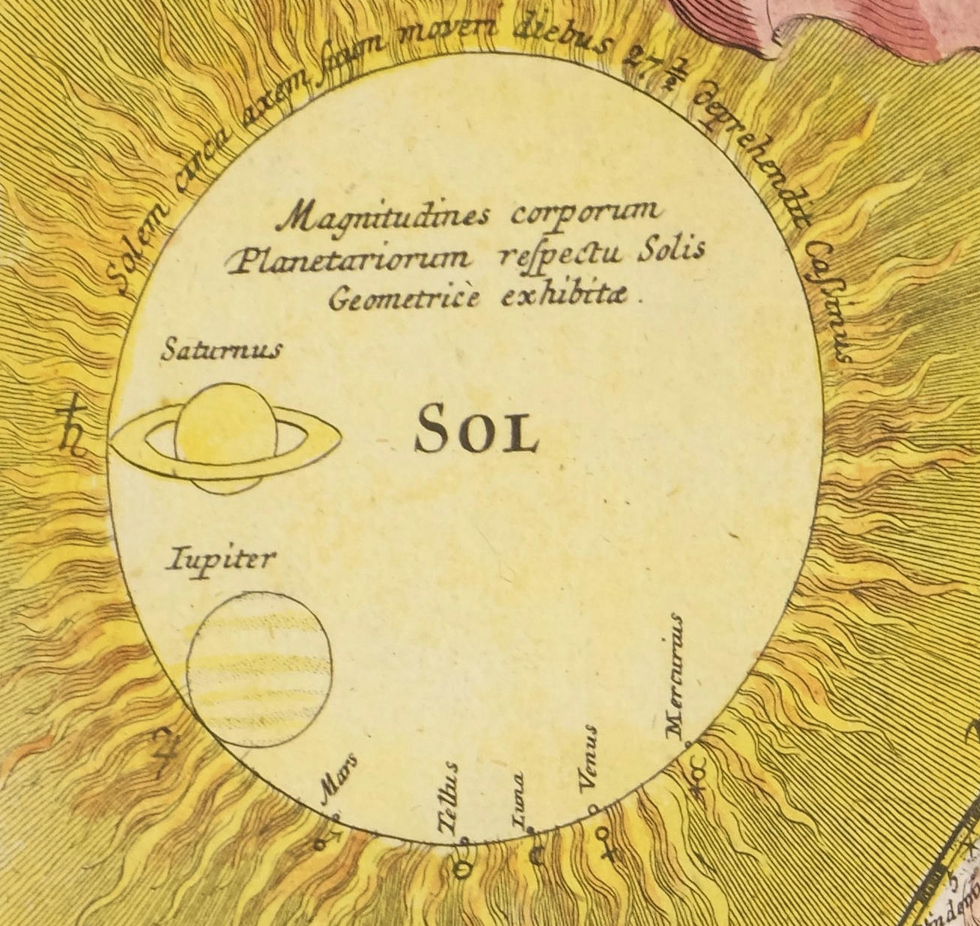

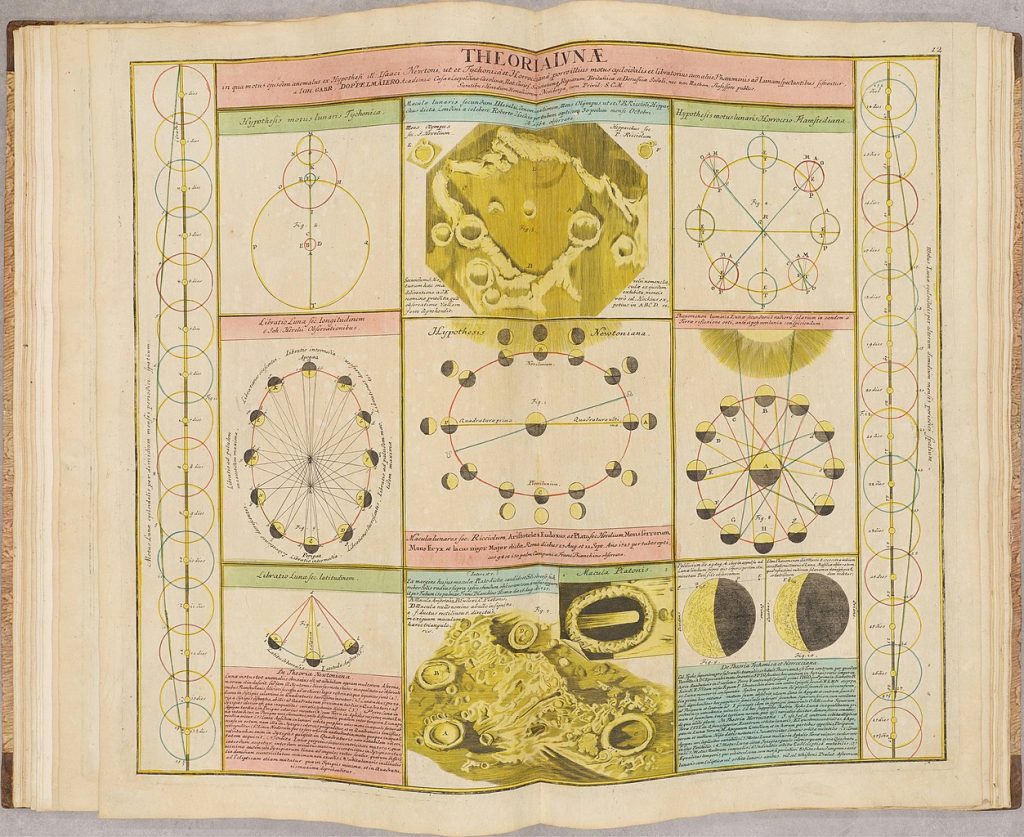

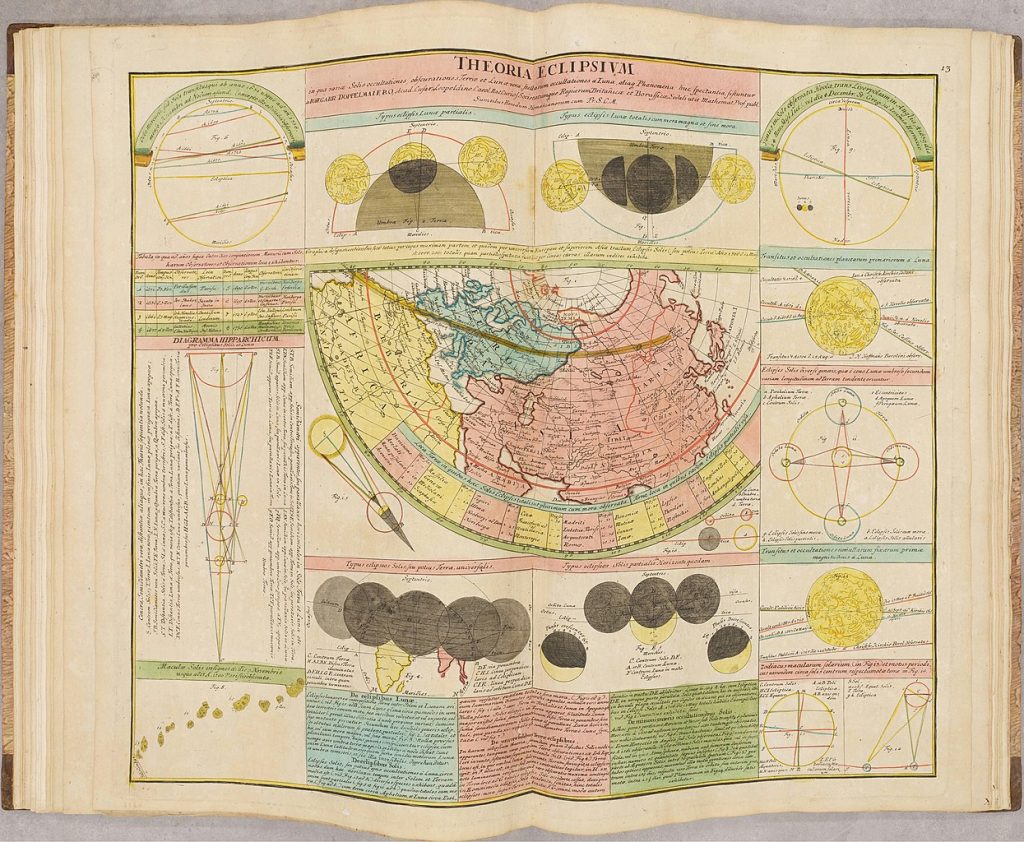

- 1742 – Atlas Coelestis (see further).

- 1744 – Neu-entdeckte Phaenomena von bewunderns-würdigen Würckungen der Natur : welche bey der fast allen Cörpern zukommenden electrischen Krafft und dem dabey in der Finstern mehrentheils erscheinenden Liecht einige berühmte Mitglieder der preisswürdigen köngl. engl. Societaet der Wissenschafften vornemlich aber, Herr Hauksbee und Herr Gray in Londen und nach einer weitern Untersuchung, Monsieur du Fay in Paris durch viele Experimenta, zu unsern Zeiten glücklich hervorgebracht, und in unterschiedlichen Wercken dem Publico mitgetheilet [e-rara link].

Together with Johann Georg Puschner (1680-1749), a Nuremberg instrument maker and copper plate engraver, Doppelmayr published terrestrial and celestial globe pairs in 1728 (32 cm diameter), 1730 (20 cm diameter) and 1736 (10 cm diameter). The celestial globes were drawn for the epoch 1731.0, the same epoch which he used for the celestial charts in the Atlas Coelestis(plates 16-25).

These globes were re-issued in the 1750’s by Puschner’s son and, again, in the 1790’s, when the copper plates passed into the hands of the Nuremberg publisher Wolfgang Paul Jenig (1743-1805). Although the terrestrial globes were updated in these later re-issues, the celestial globes were left unchanged.